Study Guide Social Hierarchies

Table of Contents

Church Hierarchies

The Puritan Church of colonial New England was a striking paradox: it was at once remarkably egalitarian and simultaneously marked by rigid social order. On the one hand, Puritans disdained the hierarchies of the Anglican and Catholic church: there were no bishops or Popes to stand between the minister and God. Instead Puritans relied upon scripture to formulate the strict chain of command between God and the constituents of his cosmos: “Ranked under the God head are Puritan divines [ministers], then males, females, children and servants....Society's smooth operation depended on the cooperation of each … in assuming the special and assigned duties and responsibilities of each one's place” (Davies 52). This basic order of God, minister, men, women, and children underlies the symbolic structure of Indian Converts.

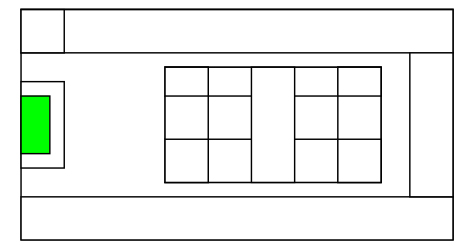

At the top of the church hierarchy were ministers and deacons. Most New England ministers had graduated from college, a privilege only available to the most gifted and the wealthy (Field 1-2). Their control over their flocks has been characterized as a “cultural domination”: colonists not only respected and revered ministers, but also supported them through obligatory taxes and mandatory church attendance (Field 15-16). Ministers provided advice to the General Court and governor, and their sermons played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and policy (Field 16-17). Second in command to the minister were his deacons, laymen who assisted the minister. An important social role of the deacon was to be part of the seating committee that mapped out the social hierarchy of the congregation: church membership, age, gender, race, wealth, public office, education, and reputation all were calculated to determine where each congregant would sit (Archer 60). The closer the person sat to the minister, the higher his social (and presumably spiritual) status. For example in the floorplan of the Rocky Hill Meetinghouse (1785) at right, the congregants could be placed in pew boxes close to or far from the pulpit (green). The goal of the seating arrangements was to have the social world reflect the spiritual realm a closely as possible. When Experience Mayhew notes in Indian Converts that someone was a selectmen, town clerk, magistrate, or deacon, he is helping his readership mentally place the individual within the community’s spiritual seating plan.

to determine where each congregant would sit (Archer 60). The closer the person sat to the minister, the higher his social (and presumably spiritual) status. For example in the floorplan of the Rocky Hill Meetinghouse (1785) at right, the congregants could be placed in pew boxes close to or far from the pulpit (green). The goal of the seating arrangements was to have the social world reflect the spiritual realm a closely as possible. When Experience Mayhew notes in Indian Converts that someone was a selectmen, town clerk, magistrate, or deacon, he is helping his readership mentally place the individual within the community’s spiritual seating plan.

Church membership was not absolutely required for civil offices, but it greatly enhanced one’s chances of being elected (Archer 69). Like the church, civil government was also stratified by age, wealth, gender, race, and reputation and was divided into several levels: (1) colony-wide officials (governors, deputy-governors, assistants), (2) town officials (selectmen, town clerks, and constables), (3) freeman who had never held office, (4) non-freemen, and the (5) disenfranchised (women, children, servants, and slaves) (Archer 70). Although it was uncommon for town officials to make the leap into colony-wide government, colonial New England society is best characterized as “stratified but not petrified” (Archer 66, 72). Children matured, indentured servants could be freed, and money could be made. Perhaps most notably, the only categories that were relatively static were those of sex and race. As Indian Converts attests however, even here God’s seating plan could override that of the civil government. Not all souls were equal in the heavenly church, but only the saved would be admitted, regardless of where they sat on earth.

Items Related to Church Hierarchies in the Archive

Magistrates & Guardians < Previous | Next > Kinship