Study Guide Social Hierarchies

Table of Contents

Magistrates and Guardians

A number of the men in Indian Converts were magistrates. To be a magistrate entailed the power to enforce white colonial legislation upon Native communities. Native magistrates, like their white counterparts, adjudicated suits for sums under 20 shillings, punished drunkenness, swearing, lying, theft, contempt towards ministers, and church absence (Kawashima 29). In this sense Magistrates usurped at least in part the power and prerogative of the sachems and ahtaskoaog (principal men, nobles) to govern and make decisions for the Wampanoag community. Some of the early Indian magistrates came from noble families and hence may have seen the position of magistrate as a way of continuing their family’s traditional role in island life. Others, however, came from less notable families. Either way, at least some of the Indian officials on the island were chosen by the community rather than solely by the white colonists: in this sense, this new ruling class continued the tradition of authority through consent not force.

The new status and authority of the court was physical as well as political. Courts were an integral part of New England society: a brick or wood courthouse stood at the town center of the county seat with the pillory, whipping post, and jail nearby (Hoffer 27-28). The public presence of these symbols of dominance undoubtedly discouraged crime. Courts, however, also helped build communities. Court days were a great spectacle in which jurors, witnesses, lawyers, spectators, and the accused all gathered to watched and participated in the proceedings to determine insider and outsider status (Hoffer 27). The courts not only established the legal boundaries of appropriate and acceptable behavior, they regulated taxes, fees, fines, and even the public roads (Hoffer 29). Starting in 1658, the General Court encouraged praying towns to choose Indian magistrates to hear minor civil and criminal cases (Kawashima 28, 245). Magistrates joined together to form higher Indian court to which appeals were made. Appeals from this court were turned over to the white Court of Assistants (Kawashima 29).

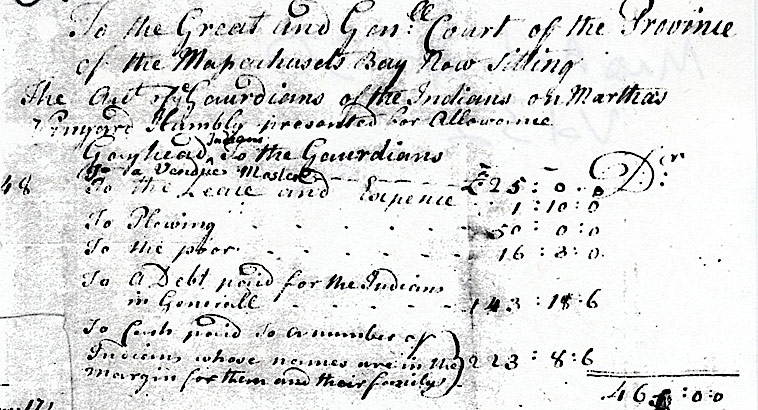

Rather quickly colonists sought to curtail the limited autonomy and authority they had given to Indian courts and magistrates. In 1694, colonists passed an act in Massachusetts “for the Better Rule and Government of the Indians in their Several Places and Plantations” (Kawashima 32). This act allowed the colonial governor to appoint white justices of the peace (or “guardians”) that would have wider and more extensive ministerial power over Native communities (Kawashima 32). These rights were extended over the course of the eighteenth century to include the right of the guardian to take and allot Indian lands. Three of these guardians were appointed to the island of Martha’s Vineyard (Kawashima 32-33). This system led to many abuses and Wampanoags and others lodged complaints against the guardians and the system more generally, both on and off the island (Kawashima 33, Campisi 83). In the best case scenario, however, guardians served as informal legal advisors and attorneys in many of the cases that arose between Wampanoags on Martha’s Vineyard and their white neighbors (Kawashima 182). For example in 1698 white attorney Matthew Mayhew defended Isaac Ompanet in a suit brought on by Simon Athearn. Athearn sued Ompanet for eighty pounds for building a wigwam near Athearn’s house. Although Ompanet originally lost the case, it was overturned on appeal and Ompanet was awarded the land, damages, and the cost of the suit (Kawashima 188-89). It was not uncommon for Indian litigants who lost cases or won small awards on the Vineyard to do better off-island on appeal, in part due to the jury system (Kawashima 190-91). In general, however, the court system did not favor natives. The transformation from sachemships to English civil authority, however, was a slow process of negotiation in which Indian converts and magistrates played a crucial role.

Rather quickly colonists sought to curtail the limited autonomy and authority they had given to Indian courts and magistrates. In 1694, colonists passed an act in Massachusetts “for the Better Rule and Government of the Indians in their Several Places and Plantations” (Kawashima 32). This act allowed the colonial governor to appoint white justices of the peace (or “guardians”) that would have wider and more extensive ministerial power over Native communities (Kawashima 32). These rights were extended over the course of the eighteenth century to include the right of the guardian to take and allot Indian lands. Three of these guardians were appointed to the island of Martha’s Vineyard (Kawashima 32-33). This system led to many abuses and Wampanoags and others lodged complaints against the guardians and the system more generally, both on and off the island (Kawashima 33, Campisi 83). In the best case scenario, however, guardians served as informal legal advisors and attorneys in many of the cases that arose between Wampanoags on Martha’s Vineyard and their white neighbors (Kawashima 182). For example in 1698 white attorney Matthew Mayhew defended Isaac Ompanet in a suit brought on by Simon Athearn. Athearn sued Ompanet for eighty pounds for building a wigwam near Athearn’s house. Although Ompanet originally lost the case, it was overturned on appeal and Ompanet was awarded the land, damages, and the cost of the suit (Kawashima 188-89). It was not uncommon for Indian litigants who lost cases or won small awards on the Vineyard to do better off-island on appeal, in part due to the jury system (Kawashima 190-91). In general, however, the court system did not favor natives. The transformation from sachemships to English civil authority, however, was a slow process of negotiation in which Indian converts and magistrates played a crucial role.

You can read more about Indian magistrates and their families in the biographies on Samuel Coomes, Japheth Hannit, William Lay, Joseph Mittark, John Papamek, Miohqsoo, Abel Waumomphuque Sr. and Wuttinomanomin in Indian Converts (95, 116, 119-22, 126, 141-42, 154, 160, 173, 176-77, 185, 188, 192, 195, 229, 236, 285, 303).

Items Related to Magistrates and Guardians in the Archive

Hospitality < Previous | Next > Church Hierarchies