Study Guide Island Christianity

Table of Contents

Meetinghouses

One of the great innovations of Puritan worship was the symbolic structure of the meetinghouse. Meetinghouses differ from churches in that meetinghouses are used for secular and religious purposes, while churches are primarily places of worship (Sinnott 5). Unlike Catholic and Anglican churches, Puritan meeting houses emphasized the Puritan plain style and the distrust of church hierarchy. Puritans rejected the ornamentation characteristically found in of Catholic places of worship, as they feared its ties to worldly vanity and its capability to distract worshippers from God. This distrust of ornamentation led to a “plain style” that is found in Puritan literature, architecture, furniture, and arts. Puritan divine John Cotton put it best when he proclaimed, “God’s altar needs not our polishings” (Preface to Bay Psalm Book). Puritan meetinghouses reflected this devotion to simplicity and humility, as well as the distrust of Catholic icons like the cross. While Renaissance churches commonly are laid out in the form of a cross, and use the structural ratio of 4:3 to emphasize the movement of the worshipper from the earthly realm [4] to the spiritual realm [3], Puritan meetinghouses were typically square or rectangular. Instead of stained glass windows, window panes were clear, allowing for the intense sun of New England summers to beat down upon worshippers and inspire them with god’s unadulterated magnificence. Up until the nineteenth century, meetinghouses were usually unheated and were so cold that the baptismal water and the communion bread often froze (Sinnott 11). Pews were narrow, and most prayers were performed while standing (Sinnott 9-11). Puritans sought to break free of the chains of the flesh, rather than to pamper them.

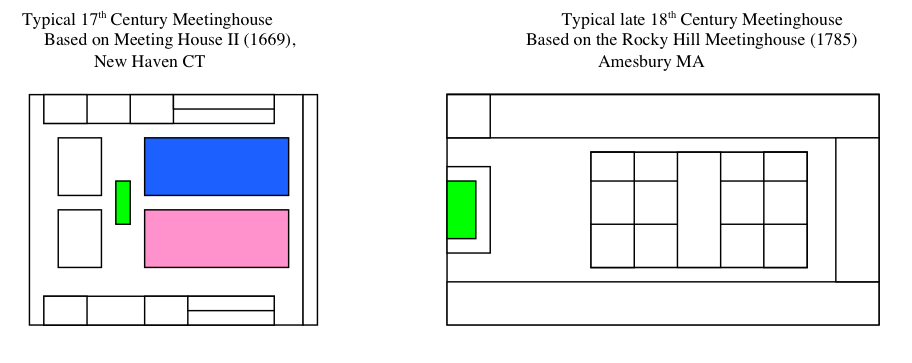

Meetinghouses reflect the Puritan distrust of church hierarchies. Rather than placing the pulpit at the back of the church so that it had to approached like an altar, the pulpit was placed in the center of the building with the pews surrounding it in a less sacerdotal manner (see below). Every member of the community, regardless of race, class, or gender, were allowed and indeed compelled to attend, and all church members had a vote at meetings (Sinnott 6-7). While for later generations the de-emphasis on church hierarchy would be seen as a harbinger of American democracy, for Puritans, the place of worship was socially marked in important ways. Seating in meetinghouses reflected social values, with the pews closest to the minister being given to those of more revered “age, wealth, birth, learning, and public service” (Sinnott 7-8). While in the earliest meetinghouses, such as second meetinghouse in New Haven, Connecticut (1669; shown below on the left), women (pink) and men (blue) sat on rows on benches on opposite sides of the house (Donnelley 70), in later congregations families sat together in pew boxes (shown below on the right) Green boxes below indicate the pulpit from which the minister preached.(1)

Figure at left based on Ezra Stiles' plan (Donnelley 70)

It is likely that the meetinghouses on Martha’s Vineyard followed this general pattern of change. Another common meetinghouse feature was the small upper gallery reserved for slaves, African Americans, and Native Americans (Sinnott 7). Racially mixed congregations on Martha’s Vineyard that whites and Wampanoags probably also sat separately. Such divisions must have had an impact on Wampanoag converts sense of self and their relationship to the body politic, and may have explained in part the preference for Wampanoag-led congregations. The assumption of racial inequality is also present in the introduction to Mayhew’s Indian Converts as well as throughout the text.

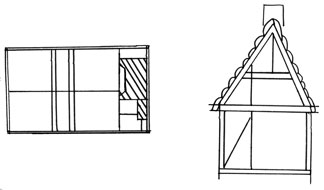

Hancock-Mitchell house. Quansoo, Chilmark (based on Scott figure 15A)

When considering the early meetinghouses on the Vineyard, it is worth keeping in mind the larger Puritan ideals of simplicity, social status, and innovation. Early church services appear to have been held in the oldest section of the Hancock-Mitchell House (shown above), which some conjecture was built by Reverend Thomas Mayhew Jr. as a one-room meeting house for the Wampanoags living in Chilmark and Takemy (Scott III.186-187). By 1666, however, land had been set aside for a proper meetinghouse, the location for which is given on Simon Athearn’s Map of Tisbury (1694). This structure would have been the place of worship for Thomas Mayhew Sr., John Mayhew, and Experience Mayhew. In 1701, congregants elected to build a new meetinghouse "after the manner and dimensions of the meeting house in Chilmark" and "to build the same meeting house as Cheap as they Can." (Kraetzer 1986). This reflected a more general New England practice uniformity amidst change: as historian Edmund Sinnott notes the “most frequent instruction of a society to its building committee when they were about to erect a new meetinghouse was to fashion it after the one in such and such a town” (Sinnott 10). While the floorplans for both the original meetinghouse (1666), and the meeting house in Chilmark and Tisbury (1701) are now lost, it is reasonable to assume that they reflected the general movement from the early square type to the rectangular with a taller spire. As Jonathan Fletcher Scott’s reconstruction of the early Wampanoag meetinghouse (1655) in Chilmark demonstrates, places of worship were simple and unostentatious. Other non-Puritan island churches, such as the Baptist Church, reflect these early ideals. Organized in 1693, the Gay Head Community Baptist Church is the oldest native Protestant church in continuous existence in the country. The congregation began as a part of the “antipedobaptist” splinter off of the congregational community. When the church was rebuilt, the old rafters were reused in a nearby house. Legend has it that household could sometimes hear Wampanoags singing hymns of praise ("Aquinnah").

Notes

Items Related to Meetinghouses in the Archive

Island Sermons< Previous | Next > Sabbath