Study Guide Reading Gravestones

Table of Contents

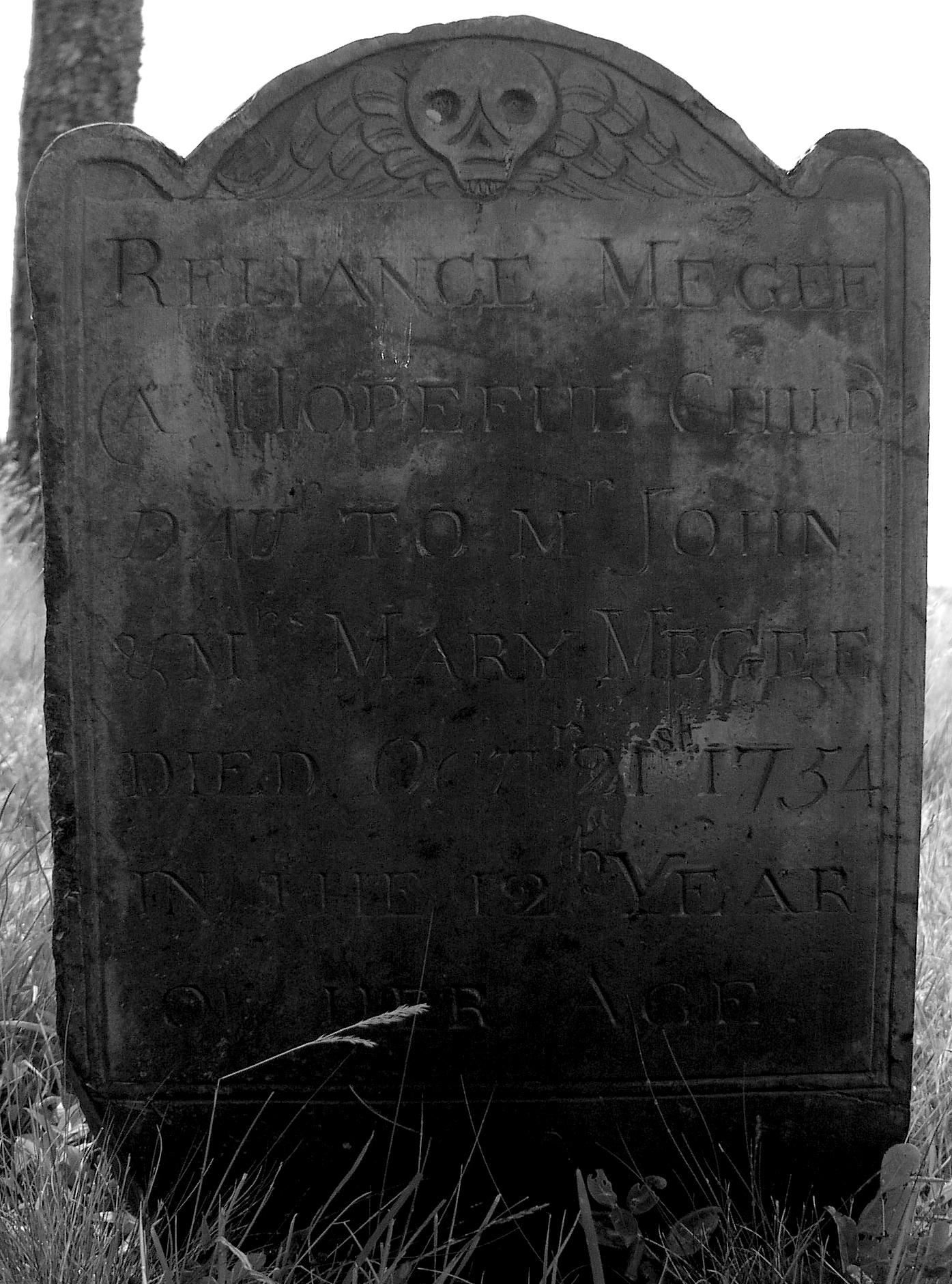

MODEL INTERPRETATION: Reliance McGee, “A Hopeful Child”

- What does it say?

- Whose stone is this?

- Where was it found?

- What is the stone's shape?

- What does the inscription tell me?

- What does the iconography of the borders, lunette, and finials tell me?

- Who was the carver?

- What can nearby gravestones tell me?

- Putting it all together

A. What does it say?

|

RELIANCE MEGEE DAUr TO Mr JOHN DIED OCT 21 1754

|

B. Whose Stone is This?

Reliance Megee (McGee) was the granddaughter of Rev. Experience Mayhew, the author of Indian Converts. Her parents are mentioned in Charles Banks’ History of Martha’s Vineyard (see a portion of the family genealogy online at <http://history.vineyard.net/mayhew.htm#experience60>). Her father John McGee was also a minister.

C. Where was it found?

The stone is located in the West Tisbury Village Cemetery on Martha’s Vineyard. The earliest stone found in the cemetery is that of Reliance's great-grandfather, John Mayhew, whose stone was featured in one of quizzes. (Richardson 180). John Mayhew's stone had a death's head, and cherubs did not begin to dominate the island's gravestones until after the 1750s. Click here to see a seriation

chart of the cemetery (Iarocci 153).

West Tisbury was a primarily white settlement, and like most of the people interred in the West Tisbury Cemetery, Reliance McGee was an Anglo-American Protestant. In 1680 the population of the town was about 120 people, but by 1765 the population had grown to 838 people living in 110 houses. Of these only 39 were (Wampanoag) Indians, and 9 were African American (possibly slaves). In 1790 the population was 1,135 whites and seven "other free people," whom Banks presumes are African Americans (Banks HMV II.West Tisbury .5-7). Early settlers included Simon Athearn, Edward Cottle, Joseph Daggett, Henry Luce, and Thomas Look, many of whose descendents will be familiar from the the discussion of the kinship in the Study Guide. John Mayhew as well as his son Experience Mayhew preached at the meetinghouse in town. Other ministers included the "orthodox" (but often drunken) Josiah Torrey, Nathaniel Hancock, and Samuel West. In the early 1800s Methodists and Baptists opened churches in town as well.

D. What is the stone's shape?

The stone is vertical and in the shape of a tablet. It has a plain border and very small undecorated finals. The shape of the stone is very typical of the West Tisbury Village Cemetery during this era (seriation chart). The simplicity of the stone (as compared with say that of her great-grandfather JOHN MAYHEW [1688]) is typical both of the 1750s and of stones for children.

E. What does the inscription tell me?

The inscription has the following elements:

| RELIANCE MEGEE | 3. Name |

| (A HOPEFUL CHILD) | 2. Epithet |

| DAUr TO Mr JOHN | 2. Epithet |

| & Mrs MARY MEGEE | |

| DIED OCT 21 1754 | 4. Formula of Death, 5. Date |

| IN THE 12th YEAR | 7. Age |

| OF HER AGE. |

Thus the order of the inscription is 3, 2, 2, 4, 5, 7. Interestingly enough,

the stone has no header. During this era we would expect to see either “in

memory of” or “Here lies [buried] the body [corruptible, what was mortal]

of.” Sometimes children’s inscriptions are shorter, so this may explain

the lack of header. The use of the optimistic epithet “a hopeful child”

nicely balances against the winged death’s head.

F. What does the iconography of the borders, lunette, and finials tell me?

There is only one image on the Reliance McGee stone: a winged death’s head. The proportion of death's heads to cherubs varies over time by cemetery and area: for example, in 1750s all of the gravestones in Stoneham, MA had death's heads, while in Newport, RI, cherubs were popular much earlier (Deetz fig. 1; Luti 41-42). In general, though, "The earliest occurrence of cherubs is in the Boston-Cambridge area, where they begin to appear as early as the end of the seventeenth century.... The farther we move away from the Boston center, the later locally manufactured cherubs make their appearance in numbers" (Deetz). However, some early cherubs made it from Boston to the island of Martha's Vineyard, probably through sea trade: the earliest Cherub on Martha's Vineyard is the that of Doctor Thomas West (1706), and it is found in the West Tisbury Cemetery (Richardson 182). Overall on Martha's Vineyard between 1754-58, 67% of the stones had death's heads rather than cherubs. West Tisbury is more conservative than other island cemeteries: 75% of the stones in West Tisbury between 1754 and 1758 have death's heads (Iarocci 155). Although McGee's stone is not atypical of the cemetery for these years, her parents clearly had a choice about what kind of image to use. The use of the death’s head by the Mayhew clan in an era of turmoil should be read in light of the argument about “Regular Lights” in the introduction to Indian Converts (3-4, 14-15).

G. Who was the carver?

This stone was not signed. The stone is not an elaborate death's head like the one's carved by the Lamson family that are often found on the island (Richardson 181). Rather it is a simple skull with triangle nose, like that found on children's graves in Edgartown. It is similar to other stones created by the Foster Family Carvers for Vineyarders in this era.

H. What can nearby gravestones tell me?

Reliance McGee does not appear to be buried in either a children’s row or a row of her family members, though some relations are buried nearby.

I. Putting it all together

The 1750s were an era of great religious tumult in New England when many communities either retrenched in their Calvinist beliefs or gave them up in favor of a more “liberal Christianity” that provided the solace that more Christians could count upon being saved. Some members of the Mayhew family, such as Experience Mayhew’s son John were at the forefront of this shift towards liberalism. How did members of the Mayhew family who stayed on the island, however, relate to this religious tumult? The gravestone of Reliance McGee (1754) suggests that at least some of the Mayhew clan clung to the Calvinist faith of their ancestors.

Reliance McGee’s stone is a simple vertical stone befitting a child. The

inscription is brief and the images plain: there is only a simple winged

death’s head on the lunette. The lack of hopeful vegetative images is balanced

however, by the epithet “a hopeful child.” Moreover, while the death’s head

is not as cheerful as cherubs from the cemetery (e.g. Dr. Thomas West [1706]), Its teeth are less fierce than say that of Edward Hammett (1745) or Josiah Torrey (1723). Although perhaps grim when compared

to children’s stones from other cemeteries from this era (e.g. Isaac Lopez,

Peter Cranston Jr.) Reliance’s stone comes across as tastefully optimistic

within the context of the cemetery.