Minimalist on Maximum Overdrive

Robert Morris ’58

November 28, 2018, in Kingston, New York, of pneumonia.

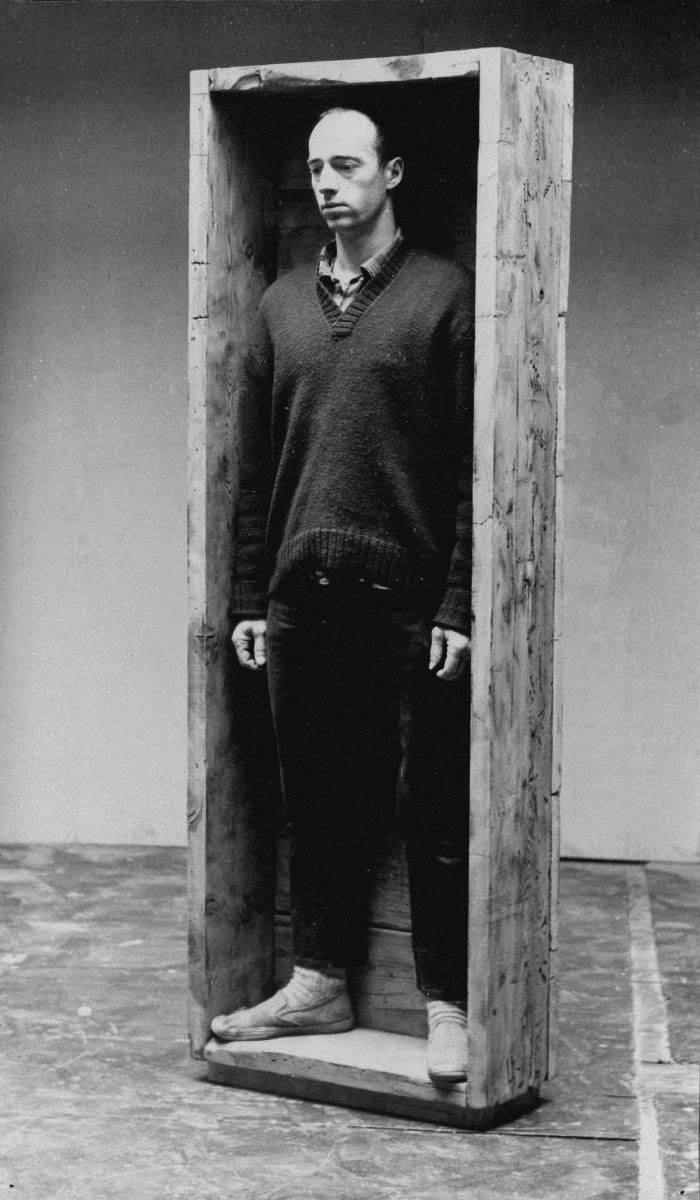

A key innovator of the minimalist and conceptual art movements, Robert Morris was one of the most influential artists of the ’60s and ’70s, redefining the concept of “artist” with a career that also included dance, performance art, and earthworks.

In a 1968 article titled “Mastery of Mystery,” Time magazine postulated that museumgoers might think there were several Robert Morrises: “There is the one whose grey Fiberglas L shapes won a prize at the Chicago Art Institute in 1966, and the one whose knife-edged I-beams starred in the Guggenheim Museum’s sculpture show last year. Then there is the Robert Morris who electrified Buffalonians at the 1965 Festival of the Arts by a ‘dance’ in which he and a female partner inched across the stage, locked in embrace and clad only in mineral oil. All these adventures were, in fact initiated by the same Robert Morris, a Buster Keaton-faced Kansas Citian.”

He grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Kansas City, Missouri, where his father worked in the livestock business and his mother was a devout Christian Scientist. When he was an adult, she remarked to him, “Well, Bobby, we all believe in something. I believe in God and you believe in nothing.”

It wasn’t that he believed in nothing—he was a minimalist and he practiced at the altar of art. An early artwork was a knot board he made in Cub Scouts. Oval in design, it featured basic knots tied in three-eighths-inch hemp rope, carefully tacked to a shellacked board. He looked forward to advancing to splices and double sheet bends in the Boy Scouts at Graceland Grade School, but this was not to be. During the second meeting he attended, the older scouts mutinied and threw Mr. Garrett, the scoutmaster, down a flight of stairs and out into the schoolyard. The scout troop was dissolved. Shortly after Robert finished high school, his mother revealed that she had chucked his Cub Scout knot board while cleaning out the chicken house.

He started college at the University of Kansas City, studying anthropology, biology, and Russian history while concurrently taking preengineering and writing courses at the Junior College of Kansas City and art classes at the Kansas City Art Institute. In those days, he went to school night and day. Moving to San Francisco, he studied at the California School of Fine Arts until he interrupted his studies to serve with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in Korea.

In 1954 he moved into a houseboat under the Ross Island Bridge and began taking classes in philosophy and psychology at Reed. Prof. Leslie Squier [psychology 1953–88] was his advisor, but it was Prof. Marvin Levich [philosophy 1953–94] who made the biggest impression. “A nonstop talker and chain-smoker who taught logic and aesthetics, Dr. Levich gesticulated and paced constantly in class,” Robert remembered. “With a cigarette perpetually dangling from his lips, he scrawled wildly on the blackboard, into which he occasionally bumped, dusting his dark, three-piece suit with chalk spots. I once saw him, while lecturing on Aristotle in his usual flailing manner, swallow the butt end of his cigarette without so much as a pause in his machine-gun delivery. I wasn’t sure he even noticed.”

Robert withdrew from Reed the next year and returned to San Francisco, where he resumed painting and had two solo exhibitions of his abstract expressionist works. He married Simone Forti, a dancer who would go on to be a leading choreographer and teacher of modern dance. They moved to New York City in 1959, joining a downtown scene made up of avant-garde painters, musicians, dancers, and performance artists. He earned a master’s degree in art history from Hunter College. He and Simone divorced in 1962.

By this time, many New York artists were disavowing the art of the ’40s and ’50s, which they considered senescent and academic. Those decades had been dominated by abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, whose monumental works seemed to reflect their individual psyches.

Robert’s work helped pioneer the language of minimalism, which avoided emotional content and emphasized anonymity over the egoic excesses of abstract expressionism. Attention was called instead to the materiality of the works and the way perception changed as the viewer moved around the sculpture, subverting the separation between art and reality and emphasizing how space joined a work of art and the viewer.

He made two versions of Untitled (Ring with Light), a sculpture consisting of two large, gray, semicircular halves joined by a narrow strip of light to form a ring. Fluorescent bulbs inside the sculpture created a bridge of light between the halves, making it appear as an unbroken unit. One version was painted plywood; the other was fabricated in fiberglass.

“I did the first fiberglass works myself in a loft on Greene Street,” he told writer Pepe Karmel. “I built an isolated room inside the loft and worked there wearing a rubber suit and complete face mask that had air pumped in from outside. It was miserable work. I sweated off about five pounds every time I laminated a work. In order to get through it I would work for 15 minutes, go out and take a big shot of whiskey, work for another 15 minutes, etc. At the end of the day I was lighter but dead drunk.”

Even if the minimalist sculptures and conceptual art he produced in the early ’60s had been all he created, he would have secured his place in the pantheon of American art. But in the years that followed, he continued to experiment with making sculptures in semitransparent materials, building labyrinths, and creating wall hangings of thick felt.

Experimenting with what he termed “anti form,” he moved away from the modular construction of his earlier sculpture and began making works in materials such as felt, thread waste, and steam. He stacked, draped, folded, hung, and cut pieces of industrial felt into towering forms that sometimes took on the appearance of alien beings. A single work held the potential to take a different shape every time it was presented, based on the arbitrary behavior of the materials from which it was composed.

He shuttered his 1970 Whitney Museum exhibition to, as he put it, “underscore the need I and others feel to shift priorities at this time from art making and viewing to unified action within the art community against the intensifying conditions of repression, war, and racism in this country.” He produced a series of monumental abstract canvases that resembled blasts from a nuclear war.

Testing the limits of what we think sculpture can be, he also worked with dirt, detritus, and other materials to create a series of land art pieces. He designed projects sculpting large expanses of land, including a long hillside piece in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and the Observatorium (1977), a massive circular form carved into the land in Lelystad, the Netherlands, which he termed “a modern Stonehenge.” He was one of eight artists selected by Washington State’s King County Arts Commission to propose designs reclaiming land wasted by industry. He transformed a former gravel pit in SeaTac, Washington, into a four-acre land sculpture, Johnson Pit #30 (1979), earning him accolades as a pioneer of earth sculpture.

In the early ’60s, he created works for the Judson Dance Theater in New York in which he occasionally performed. He was an acerbic critic, publishing essays on sculptural theory and the output of other artists. He is survived by his wife, Lucille Michels Morris.

Appeared in Reed magazine: March 2018

![Photo of Prof. Marvin Levich [philosophy 1953–94]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2022/LTL-levich1.jpg)

![Photo of President Paul E. Bragdon [1971–88]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Bragdon.jpg)

![Photo of Prof. Edward Barton Segel [history 1973–2011]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Segel.jpg)