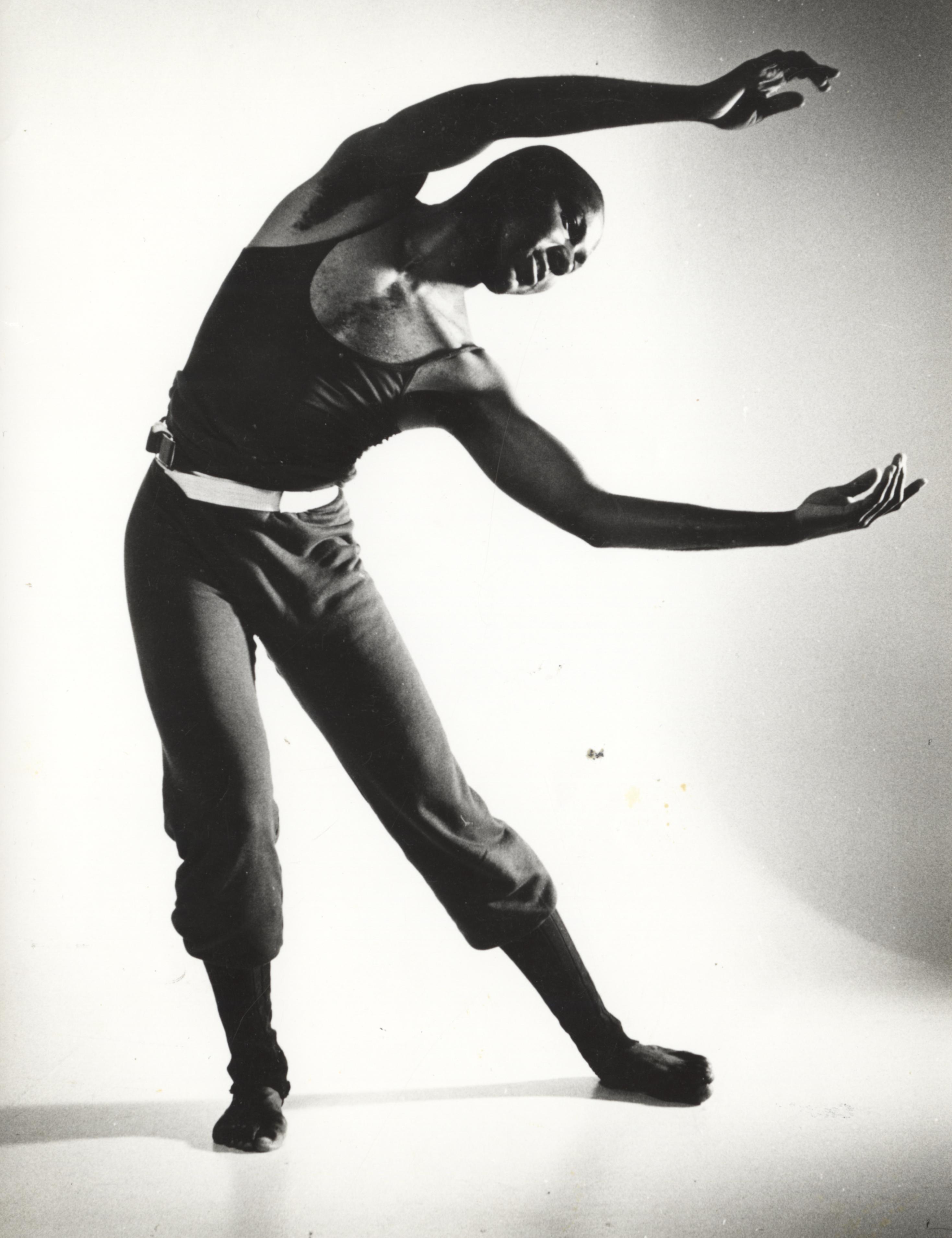

Innovative Dancer Defied Gravity

José Brown ’71

May 1, 1996, in Portland, of AIDS.

“I can never articulate in words the eternal reality—the height of buildings, the texture of cloth, the color of water, the smell of hair, the taste of fruit,” wrote José Brown ’71. “I can dance it.”

And dance it he did.

An innovative choreographer and dancer, José dazzled critics with his improbable, heartstopping moves and thrilled audiences from New York to Tokyo to Barcelona. But conventional success eluded him, and he died in Portland of AIDS at the age of 46.

He was born in Gary, Indiana—celebrated in the musical The Music Man as a “place that can light my face.” The reality is a bit less canorous. José described it as a devastated place with every fourth house in ruins, burned out, or torn down.

“Gary is a tough city, one of the toughest,” he said. “I am amazed at how famous it is all over the world as one of the world’s worst cities.”

His father died when he was seven, leaving him in a fractious relationship with his mother, Doris, who worked as a nursing assistant. Though she would marry again, give birth to José’s sister, Sophia, and then divorce, it was a lonely childhood without family friends or grandparents.

“I was probably a sissy though I didn’t know it,” said José, who later identified as gay. “I was not anti-physical; I needed a teacher. Coach Tandy was the only man who helped me.”

Doris complained of being tired. José replied that he got tired too; school was hard work.

“Six hours of school, two hours or more of homework and library time, and one hour or more of after-school activity plus household chores and getting to and from school is just as hard for a child as work is for an adult,” he recounted in a letter. “To make top grades means hard work. You did not believe this because you hated school and because you were jealous of me being smart. You thought that smart is natural. No, it is hard work—thinking takes energy. Studying takes energy. You were proud of my accomplishments, but not able to help me achieve them.”

José described the scene upon returning to Gary as an adult: “Doris was wearing a long nylon coat and had the Boston Terrier on a leash. She made this evil face to command my sister. She stood on the porch with her dog, which I pity as all the dogs she has had, and I saw how cruel she is. I fear for Doris as Sophia grows older. Revenge. Or just escape.”

Gotta Dance

“I have never sought it out,” José said. “Dancing found me.”

He came to Reed on a Rockefeller Scholarship and began his dance training with Prof. Judy Massee [dance 1968–98].

To Conrad Skinner ’74, who played piano for dance classes at Reed, José was a force of nature. “He had a broad, beaming smile and a joyousness about him that made me feel good about myself and glad to be alive,” Conrad recalled. “José would do some impossible dance move that seemed like throwing himself toward the ground and ending up parallel to it. I couldn’t believe my eyes. He defied gravity.”

After two years, José transferred to the California Institute of the Arts where he studied with some masters of modern dance. Bella Lewitzky taught him technique. He took classes from Mia Slavensak, once a leading ballerina with the legendary Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and Donald McKayle, one of the first black men to break the racial barrier by means of modern dance in the ’50s.

José moved to New York and danced with Pearl Lang’s company. Lang had been a soloist with the Martha Graham Dance Company. José would claim Graham as a spiritual and aesthetic mentor. He also performed with the Rudy Perez Dance Company, Rael Lamb’s Dance for a New World, and Kei Takei’s Moving Earth. Informed by classical Japanese dance, Takei’s choreography was a big influence on José. Another teacher was choreographer Alwin Nikolais, who opined that a dancer’s center of focus needn’t be the solar plexus; it could be anywhere on the body, even outside it. Nikolais encouraged his students to give up odd jobs and earn a living from dancing. José started his own dance company, Changing Dance Theatre, and performed in Boston and Portland.

In the mid ’70s, he moved back to Portland and opened a dance studio, Changing School of Earthhousehold Inc., in the Pythian Building on Southeast Yamhill Street. “Changing is the operative word here,” he said. “Every performance is different.” As in jazz, he wanted to give his dancers room to improvise within a given framework.

Living in a monastic cell at the Dharma House—a combination monastery and meeting place on Southeast Oak Street animated by the teachings and activities of Tibetan Buddhists—José developed a synthesis of dance styles from the various disciplines he had studied. A review of his 1977 performance at the Portland Art Museum likened him “to a magician moving on bare feet as if they were on wheels.” José held “the audience in rapt, almost worshipful attention.”

In 1978, he closed his Portland dance studio and moved to a communal farm in Oregon. The farm was beautiful, but José was not ready for it, disclaiming any interest in playing the role of guru.

“As I pulled ‘weeds’ that the Indians ate or used as medicine, as I killed off wild berries for strawberries, as we fenced out deer for goats and cows, as we dammed streams which were plentiful of fish, I saw all too clearly the curse of stability—man free from the forces of nature,” he wrote. “That I might pray for rain or fish was unnecessary when plumbing and transportation were available.”

He left the farm after several months and busked his way through Europe, including stops in Spain, Greece, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

East and West

“To get started somewhere he would dance on the streets,” his friend, Deborah Einbinder, said. “He would gather a troupe from that act. He would just dance. Put a hat out. I remember him telling that’s how he got started in Barcelona. First it was just him. And then there would be 10 of them on the street. And then they’d get a studio. And then they’d rent a hall. And then they’d get a grant.”

In India and Nepal, he lived in the Tibetan monasteries of Kalu Rinpoche, Tranger Rinpoche, and Situ Rinpoche. For seven weeks, he worked with the Tibetan Opera Company in Dharamshala, and then moved to Bangkok where he lived next to a Kampuchean refugee camp and taught dance.

Moving on to Tokyo, he taught and performed for more than four years, studying the Noh form of musical drama with Hideo Kanze. José immersed himself in Butoh—known as the “Dance of Darkness”—with one of its founders, Kazuo Ohno. Fusing extreme visual images with grotesque, hyper-controlled motions, Butoh arose from the destruction of the Second World War. While in Tokyo, he met dancer/choreographer Akemi Masaki, who recalled seeing him dance in 1975.

“His movement was like ice skating,” she said. “No one in Japan had ever seen anyone move like that … He was a sensation in Tokyo.”

Returning to Europe in 1983, José lived in Copenhagen, and taught and performed in Europe and the Philippines. While in the Philippines, he began writing a three-act dance play, Where the Moon Goes, a kind of autobiography of his inner self that he would revise and perform.

“I am attracted to the Noh theatre concept where the state of mind takes precedence to dramatic action,” he wrote. “Form and content being perfectly merged to create a state of mind in the dancer-actor whereby he/she merges into the impersonal stream of consciousness which parallels the early shamans in ritual dance and song cycles performed for the community.”

Megan Nicely ’89 took a master dance class from José in Portland and was chosen to dance in Where the Moon Goes at the Echo Theatre. Working with an almost nonexistent budget, dancers performed amidst a sea of black balloons in costumes made from long underwear purchased at the Salvation Army store.

“I found myself thrown into a completely new and not altogether understandable experience,” Megan said. “Beginning with improvisation, Brown guided us through a series of movements, including the slowest sit-up I have ever done in my life.”

Writing about the show in the Oregonian, Martha Ullman West noted, “Brown is trying hard to make East and West meet in his work, and in the dancing itself, he succeeds… Brown moved like a well-oiled machine, catlike in his jumps, seamless in his spins.”

If I Can Make it There

“I dreamt once of trying to reach that place of quiet,” José wrote. “It was over there, but there was a towering mountain in my way. I had to climb over that mountain. I have come to New York because New York is the mountain that I must climb before I can reach that place over there.”

Returning to New York in 1987, he began supporting himself doing Tarot card readings in the street. Akemi had also moved to New York and he often slept in her apartment. Never earning more than $3,000 a year, he couldn’t afford his own place. Still, he managed to wrangle financial support for the occasional Changing Dance Theatre performance. With a grant from the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, he took “Vespers Underground: Mass Transit” to the subway platforms and underground passageway in Grand Central Station. It was the first time his choreography was performed in New York. Three days later, the production was mounted at the Merce Cunningham Dance Studio.

“For ten months now, I am without a home,” José wrote a friend. “Since leaving Tokyo I have only had instability. My heart does not want to be here and only by working can I quiet myself. I am helpless here.”

Walking the streets for miles each day, he confessed, “I am a ghost. I haunt the world because I cannot leave it and I cannot live in it.”

Forging a life in the arts is never easy. To attract fellowships and endowments, a dance company must be well-established, and reputations and audiences are created by degrees. José discovered that administering a company is as taxing as the artistic side.

“I never really did the social thing anywhere and so never have developed wealthy friends,” José said. He described himself as “all intuition, a shaman, a dreamer, abstraction,” and was unable to cultivate angel investors to underwrite his productions.

The options for a small dance company were to join with an education program, tour outside its hometown, or be totally subsidized. Most countries and municipalities support only one major dance company, and as Phyllis Lamhut, who headed her own dance company, observed, “the government is committed to preserving dinosaurs.”

“The last production cost over $10,000 for seven days of performance,” José told a friend. “I owe $2,000.”

When Changing Dance Theatre performed, José did everything from working the door to operating the tape machine. One reviewer noted, “the dancer’s frequent trips to change tape cassettes was more unsettling than soothing.” The same reviewer, however, did allow that José “showed he could put together a comprehensive program and carry it through, keeping the audience’s attention throughout … when he cut loose, he could dance up a storm of dazzling beauty.”

“José was really thinking about Big Things all the time,” Prof. Massee said. “What if some angel had really come with some big foundation grant? What if there had been a MacArthur grant for José?”

Instead, he inhabited a world of coffeeshops, parks, and libraries, and searched for a place to bed down for the night. At one point, friends give him a key to their apartment building, allowing him to place a table and chair in the building’s hallway until neighbors complained. José moved his things to the building’s roof where he slept one night. The next morning, his friends demanded their key back. José was back on the street, his clothes stained and worn. “Sometimes I see the city as I see a crystal and the tramps in the street give me the knowing eye like the holy men of India,” he wrote. “My shoes now only barely keep out water. But I dance well. My leg goes no higher than ever, but no lower, and perhaps with greater ease.”

“Poverty is the only unforgivable disease,” he penned in his journal. “The rich are blessed. The rich are beautiful. The rich are right. To be rich is to know God. Whatever one does to be rich is Godliness. A rich criminal is but a minor sin compared to a poor criminal who is 10 times cursed to Hell. Such are the values of this society.”

That Place Over There

While living in Copenhagen, José was diagnosed with AIDS. He never sought treatment. When he was back in New York he wrote: “I have learned not to expect to become part of the mainstream ever. I have a limited time, so I must do exactly what I feel and nothing else.” In 1996, at the urging of friends, he came back to Portland to die (though he never admitted he was dying). He stayed first with choreographer and teacher Vin Martinez and his wife, Anna, and then moved to the home of his friends Deborah Einbender and Brian Heald. By the end of March, he moved into Our House, an AIDS hospice.

In April, George Cummings, who had worked at Reed’s sports center, took José on a walk up through Mt. Tabor, one of the city’s hills. José used a cane and moved very slowly, stopping to rest several times. They turned back before reaching the top.

“But José was very pleased with what he had done,” Cummings remembered. “It was a beginning, he said. He was making his legs and lungs work again. José wanted to go to the beach more than anywhere else. In the optimism of that afternoon, neither of us could have known that we would not walk together again.”

The following week, José’s health rapidly declined. He passed away on May 1, and a few days later seven of his friends scattered his ashes in the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of Ecola Creek. José had been planning to perform a ceremony there, though he hadn’t told anyone what it was.

“The [Bhagavad] Gita teaches renunciation and dedication to God,” José wrote a year before his death. “I no longer look for miraculous apparitions. I do not anticipate miraculous powers. I expect nothing and reject nothing and attach myself to nothing. Fire must cling to something or it will burn out. What should I cling to? Not to hope.”

The Bhagavad Gita equates desire with fire. To desire is to wish that some present condition ceases to exist and feeds the fire. Eternally living in the present without hopes or expectations quenches not only the flames of desire, but the need for future lives to realize such desires.

comments powered by DisqusFrom the Archives: The Lives they Led

Frederick Dushin ’86

Frederick, an architect and software developer, embodied the intellectually adventurous spirit of Reed throughout his life.

William Haden

As acting president of Reed from 1991 to 1992, William “Bill” R. Haden worked to strengthen Reed’s finances and improve alumni relations.

Nancy Horton Bragdon

Reed’s First Lady Whose Warmth and Leadership Were Invaluable During a Turbulent Time

![Photo of Prof. Marvin Levich [philosophy 1953–94]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2022/LTL-levich1.jpg)

![Photo of President Paul E. Bragdon [1971–88]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Bragdon.jpg)

![Photo of Prof. Edward Barton Segel [history 1973–2011]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Segel.jpg)