Aida Bogas Metzenberg ’77

March 18, 2018, in Northridge, California, from the progression of a neurodegenerative disorder.

Aida was an accomplished scientist, genetic counselor, and professor. For her last 20 years, she fought valiantly against an unknown neurodegenerative disorder and was essentially quadriplegic for 10 of those years.

She was born and raised in Berkeley, California, to parents who were both professional musicians. When asked how to pronounce her first name, Aida would respond, “It’s Aida, like ‘I eat a banana.’” After high school, she took a trip to Portland with a friend to check out the colleges. Her friend chose Lewis & Clark, but Aida applied to Reed and was offered a full-ride scholarship, which sealed the deal. And even though her high school guidance counselor had advised her, “Women don’t really go into science,” Aida pursued the sciences. She loved to sing and sang in the chorus under the direction of Prof. Virginia Hancock [music 1991–2016].

“Aida Bogas arrived at Reed as an experienced and excellent singer,” Prof. Hancock recalled. “She joined the Collegium Musicum right away and sang with us through her Reed career. I believe it was in her senior year, an attractive freshman baritone joined us, and she and Stan made an instant connection that never weakened even in the face of her serious physical challenges later in life. She continued singing beautifully for many years; I remember a video of a recital she gave with a friend, and the voice and musicianship she always had were still there.”

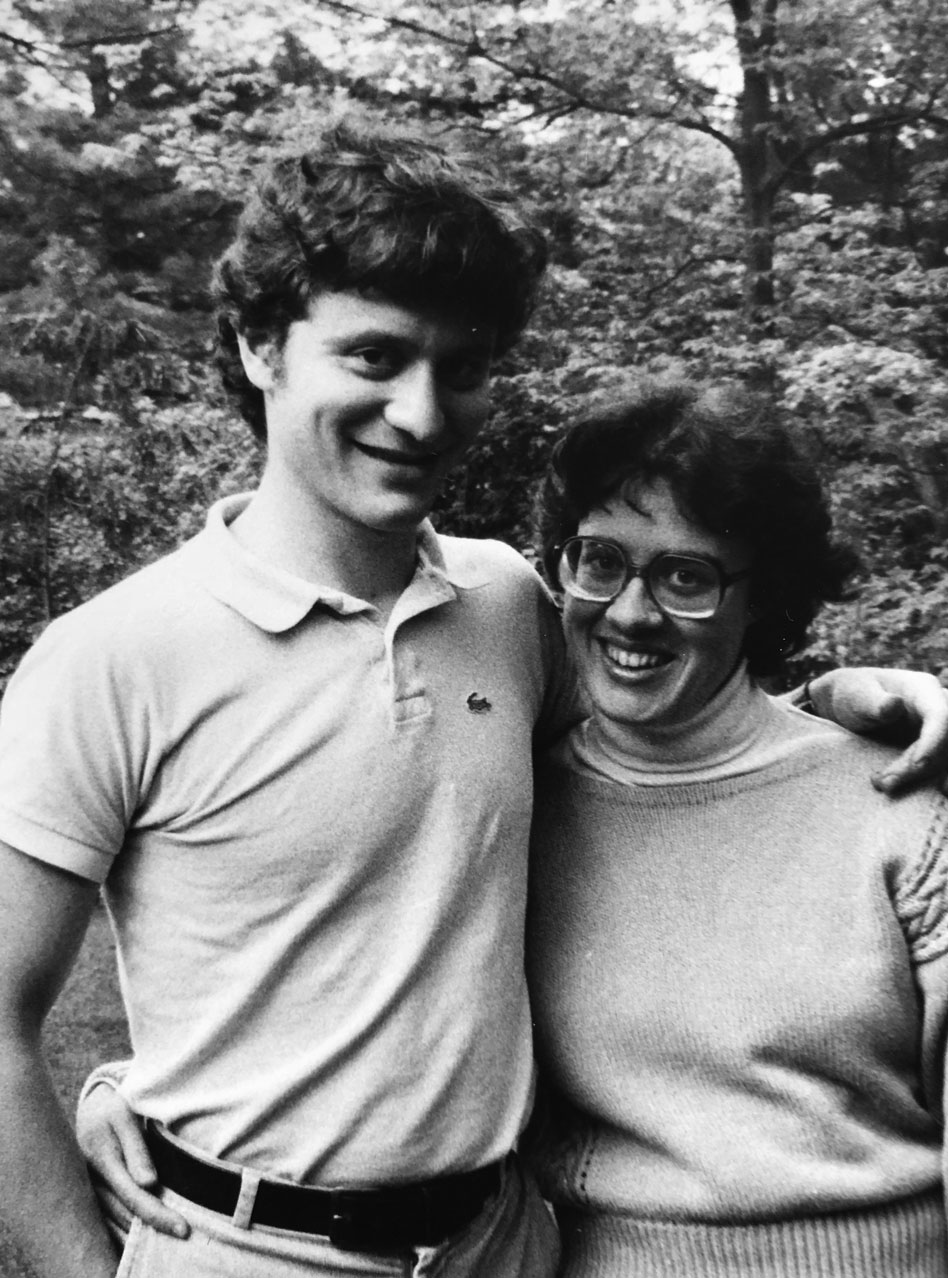

Aida was a house adviser and met Stan Metzenberg ’80 when he was a freshman.

“I think my father was pretty instantly smitten with her,” said their daughter, Gretchen Metzenberg ’07. “He could recall exactly what she wore the first day of the welcoming orientation.”

Even though Aida was dating someone else, Stan pursued her fervently, and they began dating at the end of her senior year. They married during his senior year at Reed.

Aida wrote her thesis, “Biological Effects of Radioactive Substances from Nuclear Power Plants,” with her adviser, Prof. Bert Brehm [biology 1962–93]. After graduating, she did a genetic counseling master’s program at the UC Irvine.

When Stan graduated, they both headed to the University of Wisconsin for doctoral degrees. Their daughter, Gretchen, was born during this time. Aida and Stan headed to the UC San Francisco for postdoctoral fellowships, working in research labs. Subsequently both were offered professorships at California State University, Northridge, where Aida was a professor in the biology department and the director of the genetic counseling program.

A genetic counselor meets with the family when a child is born with a genetic disorder. The counselor looks for patterns in the family tree, orders tests, and helps the family through the process. Great people skills are necessary in translating medical and scientific jargon into something a layperson can understand, and the counselor outlines what future risks might be for the child—or adult, if it’s an adult-onset disorder.

In her late 30s, Aida began experiencing such symptoms as weakness and migraines. Over the course of four or five years, her unknown neurodegenerative disorder worsened so that she used a wheelchair—eventually losing function in her arms as well. For the last 10 years of her life, she was functionally quadriplegic. Despite this, she worked full time and had a dedicated posse of assistants to type her dictations and help her run a small empire of students. One of her greatest joys was in mentoring students. With Stan’s guidance and the student help, she was able to continue teaching.

“She really pioneered online teaching at the university for big classes where she would oversee hundreds of students,” Gretchen said.

Aida would dictate and her students would do all of the computer work. She continued running a research lab and would provide guidance to students working in the lab, discussing experiments with them, helping with their theses, and doing all of the edits on their theses. When every professor had to give a formal talk about the research they were doing and Aida could no longer really vocalize, she hired an actor from the theatre department to read her talk for her. She coached him through the pronunciations, resulting in an awesome presentation.

It was ironic that Aida’s disorder followed her interest in the field. Since she knew so many people in the field, she had everything tested, but there was no pinpoint.

“We could never figure out if there was a genetic basis or if it was just an unfortunate autoimmune process or something that can’t yet be screened for,” Gretchen explained. “She lived with this a total of about 20 years, and you could not imagine someone facing it more bravely, or with more joy than Aida. She had always been a very joyful, vivacious person, and she maintained that in the face of this horrific, progressive disability. She was full of grit and continued finding joy in life, supporting people about her, and celebrating their victories.”

Aida had loved singing opera. After her disability, she wasn’t able to sing any more but would attend operas and symphonies and loved classical music. She also loved cooking. When her student assistants came to the house, she would give them cooking lessons because “most people don’t know how to cook these days.”

Aida’s life would not have been as fulfilling or meaningful without Stan, who died of a brain tumor four months after her death. Aida is survived by her father, Roy Boas; her mother, Marilyn Sherwin; her stepmother, Susan Bogas; her daughter, Gretchen; and her son, André.

Appeared in Reed magazine: June 2019

![Photo of Prof. Marvin Levich [philosophy 1953–94]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2022/LTL-levich1.jpg)

![Photo of President Paul E. Bragdon [1971–88]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Bragdon.jpg)

![Photo of Prof. Edward Barton Segel [history 1973–2011]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Segel.jpg)