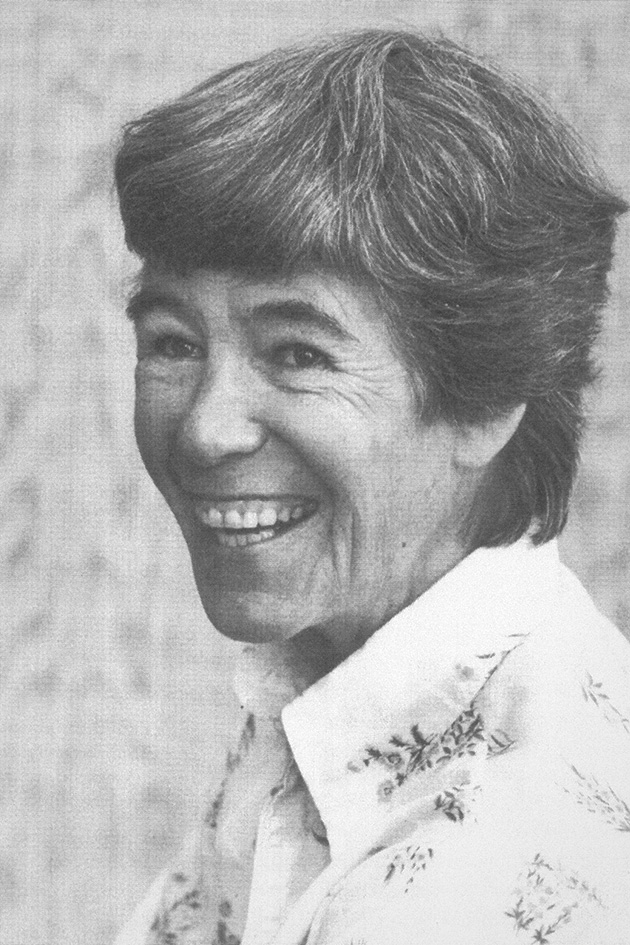

Genevieve Hall Smith ’43

Dubbed “the Naturalist Queen of the Eastern Sierra” for her writings about the history, geology, and biology of the region, Genny was a devoted conservationist who wanted future generations to experience the same joy the mountains, lakes, and birds had given her.

She was born in San Francisco in 1911 and raised in Portland. At Reed, she earned a degree in political science. Genny acknowledged that the college taught her to think, research, analyze, and be both skeptical and logical. But she wished there had been a better balance between scholarly and nonscholarly achievements.

“At Reed, I certainly gained self-confidence in scholarly and academic fields,” she said, “but overlooked just about everything else. It took a long time to realize that, while academic excellence is pleasant and worthwhile, other aspects of life are just as important, some more important, for a happy, fulfilled life. A crucial element in almost any endeavor is knowing and getting along with many people—networks, contacts. That love and friendships are more important than getting the best grades and scholarships.”

However inadequate she felt in her ability to network with others, she made up for it after leaving Reed. Genny began working in recreation: camp director at summer camps, hospital recreation with the American Red Cross in Utah, working at a community Center in Hilo, Hawaii. She married Gerhard Schumacher and began teaching in Bakersfield, California. When a local ski club introduced her to Mammoth Lakes and the eastern Sierra, it was love at first sight. She started coming to the area in the summer to hike and backpack.

In the ’50s, she and her husband acquired a cabin in the Lakes Basin. Her first guidebook started out as a simple pamphlet drawn up by a group of friends.

“Four of us, eating spaghetti one evening in my cabin at Mammoth Lakes, kicked around the idea of writing a little booklet on local mountain trails,” she said. This resulted in a 200-page book with Genny as the editor. In 1959, Sierra Club published her first book, Mammoth Lakes Sierra. Her second book, Deepest Valley, published in 1962, covered the Owens Valley. She then started her own company, Genny Smith Publishing, and continued to publish books about local history. The last book she edited, Sierra East: Edge of the Great Basin, was published in 2000.

Perhaps her greatest achievement was stopping the construction of a trans-Sierra highway that would have cut through the heart of her beloved mountains. Upon learning about the project in 1958, she began writing letters and gathering a team of like-minded activists to start what became a 27-year battle to thwart the state’s efforts to build the road. Genny networked to ensure local interests were being heard. She drew on her media resources in the outdoor community, called hiking companions and colleagues from wilderness conferences, and arranged for editorials to be written in the Los Angeles Times and the San Francisco Chronicle. She was a genius at getting local people to make their voices heard on a state and federal level, creating a coalition that included backpackers and hippie environmentalists. People drove from Mammoth Lakes to Sacramento to talk to their legislators and to the governor. As Genny noted, “It wasn’t just the tree-huggers either.” In 1972, following a pack trip through Middle Fork Valley, then-Governor Ronald Reagan announced that the road would not be built.

Genny later helped sue the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power after the city began piping water from from Mono Lake and was instrumental in limiting the amount of water that could be taken.

She coached others how to be effective as small-town political activists. “Don’t throw mud,” Genny advised. “You can have opposite ideas, but don’t make enemies; that doesn’t bring you together. Everybody deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. It’s very heartwarming to me that a bunch of political amateurs can win sometimes. Look at the Mono Lake Committee. If a little organization like that can go up against the City of Los Angeles with all its money and all its lawyers, anyone can.”

Once while advising a crew of young environmentalists working to expand Death Valley National Park, she cautioned, “Don’t trust the fat cats.” Attending a meeting between developers and local environmentalists in the Lakes Basin that included helicopter rides and an impressive spread of food, she said, “Beware, there are sharks in the water.”

In 1968, she married Ward Smith, and the couple spent summers at the cabin until his death in 1998. One of her favorite maxims was “Anything is possible until it’s proven that it’s not.”

Appeared in Reed magazine: June 2018

![Photo of Prof. Marvin Levich [philosophy 1953–94]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2022/LTL-levich1.jpg)

![Photo of President Paul E. Bragdon [1971–88]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Bragdon.jpg)

![Photo of Prof. Edward Barton Segel [history 1973–2011]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Segel.jpg)