Precision Pointe

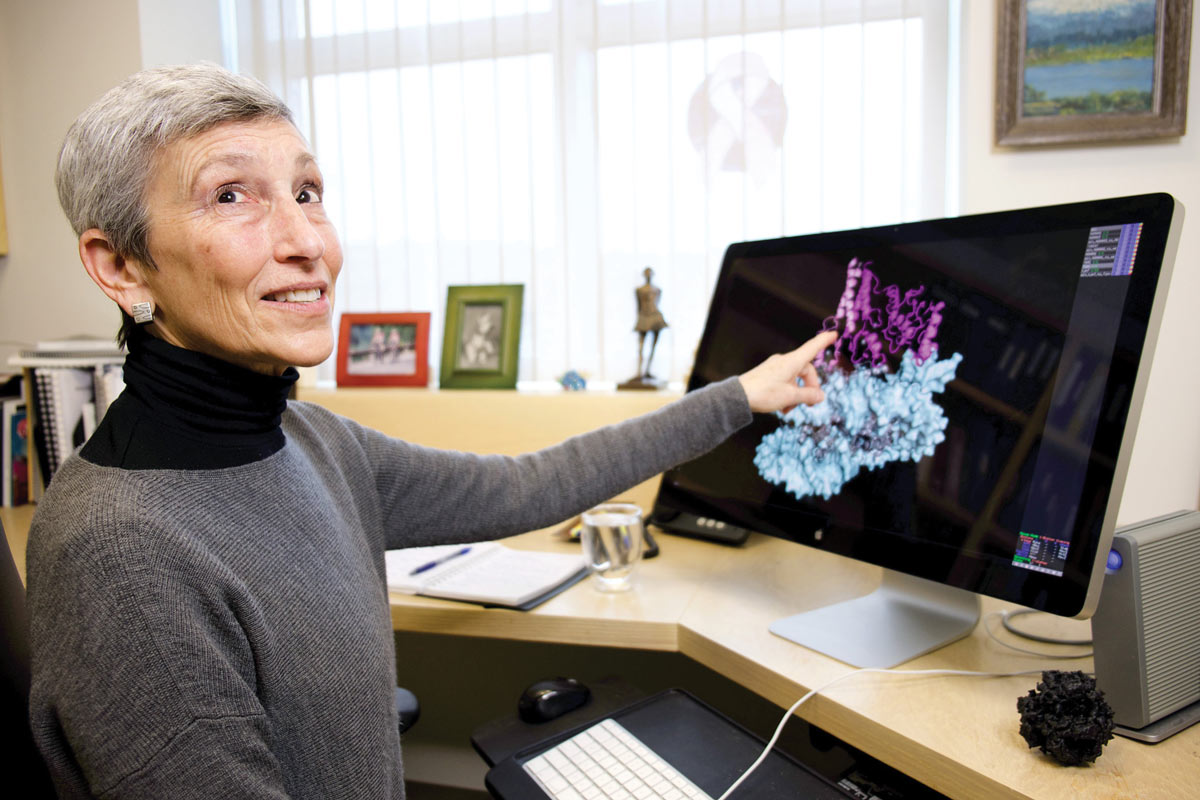

With the discipline of a ballerina, Rachel Klevit ’78 investigates the proteins implicated in disease.

How are ballet and biochemistry related? Most would probably say they aren’t. But Rachel Klevit ’78, who started her career as a semi-professional ballerina and will end it as a biochemist, disagrees. “I study the molecules of biochemistry in terms of their dynamic behavior, how they move and how their movements give rise to their function,” she explains. “You could argue a certain choreographic aspect to my own research and the way I like to think about molecules.” In 2021, Rachel was elected to the National Academy of Sciences for her research.

At the University of Washington Klevit Lab, Rachel’s research team studies the guardians of the cell. Specifically, part of the lab investigates small heat shock proteins, the first responders in a cell when some kind of stress has occurred. When protein molecules are damaged by this stress, small heat shock proteins triage the unraveling proteins. Understanding this process is key for learning how to maintain a healthy life, but also for finding therapies that may help slow down plaque buildup that leads to neurodegenerative diseases. The other part of the lab works to understand why inherited mutations in BRCA1 and its “sister gene,” BARD1, are associated with high risks for breast and ovarian cancer.

Before she became a scientist, Rachel was a semi-professional ballerina for two years with the Royal Winnipeg and Portland Ballet companies. Even as a student at Reed, she didn’t sacrifice dance in favor of a new passion for science; she simply did both. “They both require high amounts of self-discipline, of self-motivation, of focus, of being willing to practice a thing over and over again until you can do it really well,” Rachel says. That self-discipline paid off—upon graduating, Rachel became the first woman from the Pacific Northwest to earn a Rhodes Scholarship, which she used to earn her PhD in biochemistry from the University of Oxford.

Though she doesn’t dance anymore—“What is it they say? The mind is willing, but the body, not so much, right?”—one could argue Rachel still approaches her work with the precision and grace of someone who does. And she finds being multifaceted makes for better outcomes. “All the best science is interdisciplinary,” she says.

Tags: Alumni, Climate, Sustainability, Environmental, Research