Shoot for the Star

Craig DeForest ’89 is leading NASA’s PUNCH mission to make 3-D observations of an underexplored region of space: the sun and its atmosphere.

Take a walk. Everything around you—the light streaming in, the trees lining the path, the flowers blooming out of the thicket—is made possible by the sun. It’s the only star that we know can grow food, and the only one we can see clearly in the sky. We live around the sun; we work around the sun; we celebrate each time we make another rotation around the sun. But most of us hardly think about it.

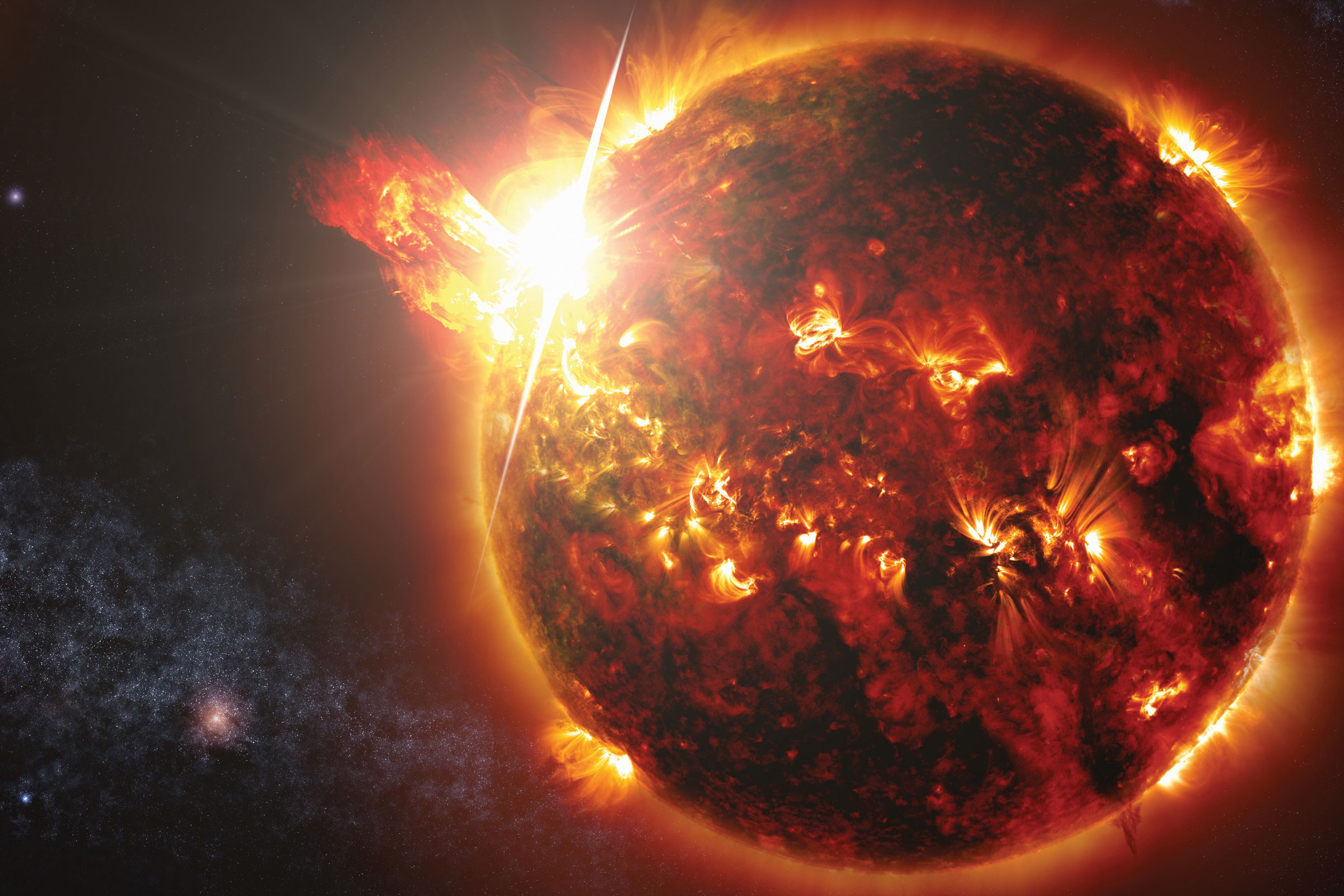

Craig DeForest ’89, on the other hand, has spent more than half his life thinking about it. “All the richness and poetry of the natural world around us—all of that is driven by this really bizarre system that’s over head every day,” he says. Soon, as the principal investigator on a NASA mission, the Polarimeter to UNify the Corona and Heliosphere (PUNCH), he’ll have the chance to see high-quality images of what he’s been studying: the sun and its environment, known as the heliosphere.

PUNCH is one of NASA’s Small Explorer missions, a program that allows scientists to pursue highly focused space investigations. Craig’s mission will send four suitcase-sized satellites up to low Earth orbit to produce deep-field, continuous, 3-D images of the heliosphere. Specifically, scientists want to better understand how the mass and energy of the sun’s corona—the outermost part of the sun’s atmosphere, which you’ve seen if you’ve ever watched a solar eclipse—become the solar wind.

The solar wind consists of protons and electrons in a state of plasma expanding outward from the sun. It affects everything in the solar system, including Earth, and it’s responsible for the northern lights, as well as the space weather that can disrupt our power grids and satellites. The PUNCH mission is the first time this phenomenon will be tracked continuously across the void, in hopes of better understanding the solar wind, the sun, and their effects on humanity.

The public often pays more attention to space missions that take astronauts to the moon. But Craig says the fact we can’t go to the sun in person doesn’t make it less interesting or less important. “We are surrounded by an enormous bubble about the size of Pluto’s orbit that protects us from the influence of things that are going on in the galaxy. That is our neighborhood, in the cosmos. It’s immensely larger than the neighborhood you walk down, you know, to go to 7-Eleven or whatever,” he says. “But it is still our neighborhood. And understanding what’s going on in it is important, right?”

PUNCH builds on prior missions, the Solar Mass Ejection Imager (SMEI) and the Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO), which demonstrated that the kind of wide-field imaging PUNCH will accomplish is feasible.

The mission’s scientists have a number of objectives. They want to better understand the solar wind—particularly how it flows, where the corona ends and the solar wind begins, and more about the natural dynamic boundary where the solar wind disconnects from the corona, called the Alfvén zone. But they also want to track and analyze the transient structures that exist in the solar wind.

To better understand these structures, PUNCH will be tracking coronal mass ejections (CMEs) across the solar system in 3-D; providing the first routine imagery of corotating interaction regions (CIRs); and capturing shocks forming and evolving in the heliosphere with unprecedented detail. CMEs are events in which large clouds of highly magnetized plasma erupt from the corona into space, which can cause radio and magnetic disturbances on Earth. CIRs, on the other hand, are large-scale regions of space that have enhanced density and magnetic field strength. These structures sweep around the sun with its rotation and typically recur once every 28 days. Like CMEs, CIRs can cause space weather that impacts Earth. But though CMEs produce stronger magnetic storms, CIRs cause them more often. The final structures, shocks, are sudden, violent changes in the solar wind, which can be caused by solar storms and CIRs. These events can sometimes lead to results that endanger astronauts in space, interfere with communications, and cause particle radiation showers on Earth.

To meet all of its objectives, PUNCH will need to take pictures of objects a thousand times fainter than the galaxy. This requires engineering a system that will block sunlight enough to take those images. Then the team will have to separate extremely faint visible features of the sky to even see the solar wind. When each image is done being processed, 99.5% of all the light in it will have been removed. “The remaining 0.5% contains the solar wind signal that we care about,” Craig says. “That is a real challenge.”

Craig is well equipped to take on these obstacles, though. He has studied the sun, its corona, and the solar wind for more than 30 years. His career has included a PhD at Stanford University, where he worked on the multispectral solar telescope array; a stint at the Goddard Space Flight Center, helping conduct the Michelson Doppler Imager experiment on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory mission; and a 25-years-and-counting career at the Southwest Research Institute, where he’s led a number of ground and suborbital instrument development efforts. Through his work, Craig developed the analytic tools that have made the current era of heliospheric imaging possible.

But another key aspect of being a scientist is an ability to communicate the knowledge you gain, which is something Craig takes seriously. Prior to becoming the principal investigator of PUNCH, he acted as press officer for the Solar Physics Division of the American Astronomical Society, and he has dedicated much of his time to making scientific concepts accessible to wide audiences. So when Craig received the funding for PUNCH, he knew he wanted to leverage the mission for societal benefit and to broaden participation in science, technology, engineering, and math by creating a robust outreach program. “We probe the universe for knowledge, and we communicate that to our fellow man,” Craig explains. “If we lack the ability to communicate to our fellow man, if we neglect the humanities, then we lose the ability to share the

knowledge and the nuggets that we find.”

PUNCH is slated to launch in April 2025 from the Vandenberg Space Force Base in Santa Barbara County, California. Craig says that more than anything, he’s excited to finally see high-quality images of what he’s been studying for so long. “Having the chance to glimpse the interplanetary void,” he says, “and see that the thing we think of as just empty space is a roiling, churning, streaming torrent of material—that is really remarkable.”

Tags: Alumni, Climate, Sustainability, Environmental, Research