Lend Me Your Ears

Open debate is crucial for democracy—even when we know we're right.

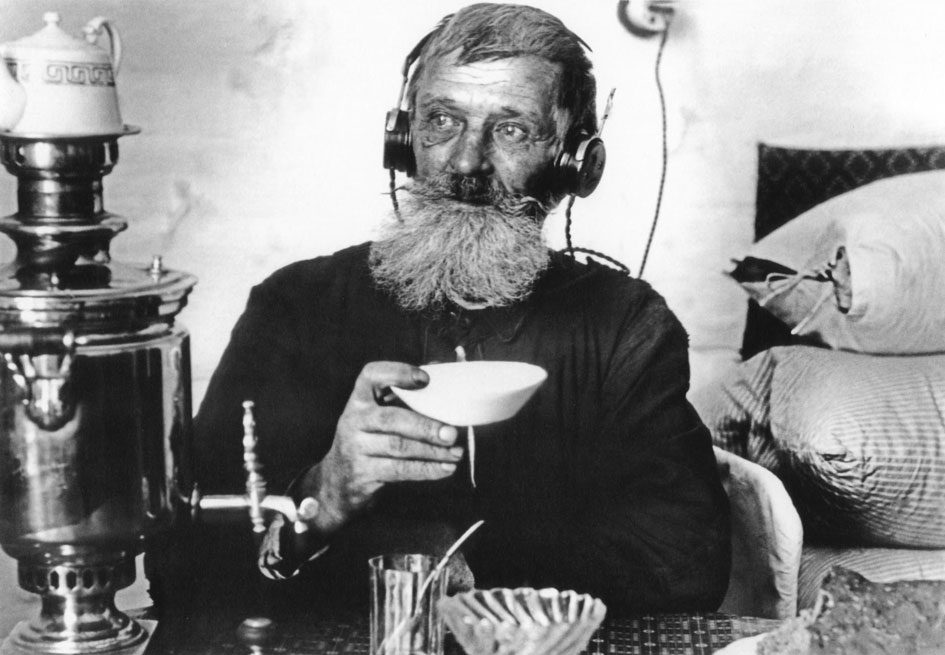

We live in the age of the digital cocoon. At the bus stop, in the gym, in the café, at the bar, we occupy the same space, but we do not talk to each other—often we do not even seem to see each other. We are too busy being absorbed. We have to monitor our Twitter feeds, keep up with the clickbait, and find out what’s blowing up on Instagram.

Anthropologists of the future will no doubt have their hands full examining how information technology is changing our human interaction in public. But what I’m really worried about is how it’s changing our political discourse. We are less and less a nation bound by common ideals and more and more an anarchy of identity groups smirking at internet memes.

Given the polarization in this country—now more extreme than ever, according to the Pew Research Center—it’s no surprise that most of our political exchanges are (to borrow a phrase from Thomas Hobbes) nasty, brutish, and short. But as journalist Bret Stephens recently wrote in the New York Times, we are in danger of losing the art of disagreement. Rather than listening to others and seeking to understand them, we either screen them out or drown them out.

Venting in the echo chamber may feel good, but it comes at a cost. More than 150 years ago, the British philosopher John Stuart Mill zoomed in on the fundamental importance of debating our most cherished ideas—even when we’re certain that we’re right.

Mill argued that fearless discussion makes our ideas stronger, not weaker. In a genuine debate, we can’t just parrot the party line—we have to figure out why we believe as we do. Our beliefs escape the paralysis of dogma and gain the force of reason.

One of the great things about working at Reed is that I get to witness this evolution up close. The starry-eyed freshman who raved about the gonzo antics of Hunter S. Thompson? By his senior year, he was an expert on new journalism and its impact on American fiction. The sophomore obsessed with video games? She’s writing a psychology thesis on games as a teaching tool. The economist besotted with microfinance? She’s in Tanzania with the World Bank.

That sort of transformation is what college is all about. But let’s not just push this project off on millennials. Fresh ideas are just as important for older people. The world is changing. Let’s take off our earbuds, step out of the cocoon, and listen to it.

Tags: Campus Life