Breaking the Frame

Students in Art 251 tackle the ultimate outsider art form—comics!

In 1954, a prominent psychiatrist by the name of Dr. Fredric Wertham warned America about a dark, insidious force corrupting the morals of an entire generation. Titled Seduction of the Innocent, Dr. Wertham’s book became a best-seller, playing on postwar anxiety about juvenile delinquents, sparked by an unlikely instrument of insurrection— the ten-cent comic book.

Today, comics—and their highbrow cousins, graphic novels—constitute a billion-dollar industry with a growing and dedicated readership among all walks of life. But comics are also a compelling and distinctive art form, with their own logic, discipline, tools, and traditions, just as worthy of study as ceramics or printmaking, if perhaps dappled with a little more gutter and shadow.

For the past two years, visiting professor Daniel Duford has taught Art 251, Making Graphic Novels, where students explore the history, structure, and mechanics of visual storytelling—and produce their own comic by the semester’s end.

“Reed students tend to be very cerebral and live in their heads, which is great—you can get to a lot of places there,” Duford says. “But a medium like comics, even though it goes back to a ‘junk’ culture, provides a space where things can become ungainly. In academic study you’re not always allowed to get into a mess.”

Visiting professors leaven the bread at Reed’s intellectual banquet by allowing departments to offer a broader range of courses, which can be changed every few years.

Most students in this popular class are not art majors, but fans of the medium, curious about both the theory and practice of comics. Practitioners of the form are known as comic book artists, or cartoonists, but even if none of his students go on to produce comics for a living, Duford believes they will benefit from having learned to think with their hands.

He refers to a favorite book, Trickster Makes This World, in which author Lewis Hyde refers to “working the joints”—effecting change in the place that bends. Hyde writes: “There is an art-making that begins with pore-seeking (lifting the shame covers, finding the loophole, refusing to guard the secrets), that uncovers a plenitude of material hidden from conventional eyes, and that points toward a kind of mind able to work with that revealed complexity.”

In mythological stories, Trickster often uses humor to cross over the boundaries that groups use to regulate social life. One of the best places to skirt boundaries is through the pores where the humors flow. Comics provide a porous place to cross over—to work the joints.

“This medium is both cerebral and physical,” Duford says. “The thinking happens through your hands, and it’s messy. Comics carry the whiff of being discredited, of being somewhat unworthy. There are attempts to elevate it, but it works best when it still has a little bit of the stink of the gutter, the junk culture that it rose out of.”

The impact of a comic doesn’t depend on flawless drawing, but on some combination of rhythm, design, language, and story.

“It can be a really clunky, awkward drawing,” Duford explains. “It isn’t important that one is able to render the human figure beautifully, or perfectly capture the roundness of a tree. If you can communicate visually, and have a design sense—meaning you understand how to make these images somehow communicate rhythm and movement—you can do a comic.”

The semester begins with studying the form. Building blocks are made up of images in boxes that form a sequence; space between the panels is called the gutter. Comics are a hybrid medium that borrow from painting, illustration, and cinema, employing terminology like “shots” for images and “sound effects” for the classic POW, ZAP, and WHAM. But the form also boasts features that are distinctively its own. To begin with, comics are both simultaneous and sequential.

“When you look at a painting, and spend time in front of it, there’s this kind of gestalt,” says Duford. “A movie, on the other hand, is watched in sequence; many images proceed in a line before you. In comics, you’re doing both.”

At the beginning of every class, Duford asks each student to draw a cartoon self-portrait before they go to work on their projects. They scratch away with pencils and pen nibs on Bristol paper as he makes the rounds, offering tips and suggestions. “I would broaden this line; a really thick line will give it more weight.”

Because graphic novels can be read quickly, there is a misperception that they are easy to create. In reality it is a labor-intensive endeavor. It took Duford several years to complete an 80-page comic novel, which can be read in less than an hour. To tap into the physical experience of making comics, he pushes his students to draw lots of pages. The class is organized so that most drawing assignments begin in the classroom and are finished as homework.

“If you’re quick enough technically I guess you could get an assignment done in class; but I don’t think anyone ever has,” says Shin Dickens ’17, a classics/religion major. “This is my most work-intensive class, but it occupies a different space in time. Before I do anything large, I start with small, thumbnail sketches to get the flow. I’m a nocturnal person and sometimes I go into the art building at 10 p.m. and work until 4 in the morning. I can’t do readings like that, but I can come in and draw like that.”

In their favorite classroom exercise, each student draws a door. They then pass their page to the next student, who has a minute to sketch a character entering the door. The paper continues to be passed on, with additional prompts for characters and scenes, until each student winds up with their original page, illustrated with a story made by everyone else.

“It’s getting at the reduction—how clearly you can notate an idea,” Duford explains. “Because there is no time to think, there’s no ego involved. Creatively it breaks you through to places you might not have gone before.”

Indeed, too much time spent on a panel stifles the energy. Or, as a French cartoonist once observed “Good drawings get in the way of good comics.” Being a sequential art, there must be a balance between descriptive information and the need to move to the next panel. The student practitioners consider, “How does the beat work in these four panels?”

“Think in terms of music,” Duford suggests. “This is the mechanics of composing; you build slowly.

Students study the works of nine cartoonists, exploring how they handle rhythm, line, and page layout. In class, they imitate these styles while listening to a recording of Sir John Gielgud performing Hamlet. The assignment includes inserting a reference from Hamlet into the finished comic.

When Duford was a kid growing up in Bridgeport, Connecticut, comics got no respect. He was chastised for squandering the money he earned mowing lawns on 35-cent comics at Kathy’s Luncheonette and Variety Store. He started college at the University of Hartford, finishing his BFA at the University of New Mexico. His wife, Tracey Schlapp, did her undergraduate work at Lewis and Clark. The couple moved to Portland in 1996, charmed by its quirky mix of microbrews and bike lanes. Daniel taught at Oregon College of Art and Craft and Pacific Northwest College of Art before coming to Reed.

“I did a lot of shows in ceramic galleries,” he says, “but I was always in the wrong place; my work never quite fit.” At the time, his drawings and ceramic works were both fairly abstract. Then he began teaching at St. Mary’s Home for Boys, a residential treatment center for at-risk youth.

“Those boys, who were from foster care and had lived hard lives, really affected me,” Duford says. “The maleness and fragility of that experience shifted me into straight figurative, narrative work. That’s when I started to make comics.”

His first showing of large, figurative ceramics and highly charged, political drawings happened to coincide with 9/11. It marked the beginning of a trajectory to narrative-based, figurative work, steeped in mythology and contemporary politics. Exploring the myths of Americana, Duford weaves folklore and fiction into alternative narratives of power, promoting the heroism of unrecognized characters.

A myth, he explains, is a story that has truth—not always quantifiable truth, but transcendent truth dealing with the beliefs and mores of a culture.

“Myth is a way of organizing experience beyond the mundane,” he says. “We’re in a time where the transcendent is mistrusted, and at least in the art world, it’s a very cynical time. The fine art world will often take a vernacular art form and put it in a museum, where it dies. I think a more interesting situation occurs when boundaries and contexts are confused.”

In Portland’s Old Town neighborhood, Duford completed The Green Man of Portland, an installation of two outdoor sculptures and eight story makers told as a poem over ten blocks. He has completing the fourth installment of the graphic novel, The Naked Boy and is looking for a publisher for the whole series as one volume.

Now Duford’s daughter is an avid comics reader. On excursions to local comics shops he shepherds her to the kids’ section because many of the books in the shops are too risqué for children.

“Comics are not really a gateway to reading,” he says. “It’s a kind of reading, and even though it seems simple, it’s actually very complex. My daughter started early with a comic called Owly, which is all images. When Owly exclaims something it’s only in symbols, like an exclamation point. But she got it. She understood even though it was pre-textural language.”

Reading comics requires that the reader simultaneously think both about the text and the image, which is a stand-in for story exposition.

Elizabeth Stallings ’18, an English major from Nashville, Tennessee, says the course helps her burnish her storytelling abilities. She loves the class, despite her lack of confidence in her drawing skills.

“I’m using a different part of my brain than I do the rest of the time at Reed, which is fun,” she says. “Making art is a different way of interacting with people, but it’s not been a part of myself that I shared with others. When you walk into this class and everyone is exposing themselves in that way, it creates a pretty special place.”

In one project, Elizabeth worked with a partner from a creative writing class, creating a comic in which the story would have to be very condensed.

“My partner and I worked together to figure out how to condense the words, and yet give it the same feel,” she says. “I’ve been thinking a lot about making things short and sweet. It’s distilling more than diluting.”

In class, students discuss how the text and images work together. Halfway through the semester, they produce and critique two-page comics they have produced featuring a splash page—a full-page, single panel that sets up the story—with a facing page of sequential panels that expand it.

During the critique, Elizabeth initially felt some trepidation at seeing her comic posted on the wall. “Oh, no! I can’t believe he’s making me do this!” she thought.

But she discovered fellow students were kind in the critique; it wasn’t a competition. “Now I don’t care,” she says. “I’m where I’m at; you’re where you’re at.”

There is a decided difference between building a character in a novel and creating one in visual construction like a comic. Take a character like Charlie Brown: his round circle of a head seems to invite empathy. Now think of a novel like Madame Bovary, composed more of interior dialogue than exposition. How would you translate it visually, using just a few lines?

In one class, Daniel passes out portions of the script for My Dinner with Andre, essentially a movie about two guys talking. Students are charged with distilling it into a comic with two characters and several scene changes.

“I love creating characters,” Shin says. “The more I work on them, the more they show personality, having wants, needs, and thoughts. Sometimes I like some element of a character, a design or idea, but it doesn’t work. But occasionally they stick around and grow into themselves.”

Comics have long been associated with superheroes, but the medium also includes science fiction, memoir, and even reporting, as exemplified by Portland cartoonist/journalist Joe Sacco. Duford’s class investigates experimental forms, such as cantastoria, a kind of street theatre where the audience chants or sings text while gesturing to an image or series of images.

In the final weeks of the class, each student creates and publishes a graphic novel. Because it is primarily a medium of reproduction, students must figure out which of the myriad methods they will use to reproduce their works. They have already learned how to draw so that the work can be scanned and reproduced.

“When I think about this class,” says Elizabeth, “I think about really being myself—not about how other people will perceive my work, which I very much did in the beginning. That has changed with the freedom to express myself the way that I want to express myself. In a discussion it’s easy for people to say, ‘I don’t agree with what you’re saying,’ since those arguments are based in fact. In the case of my comic, if you don’t like it, that’s fine, but you can’t tell me that it’s wrong.”

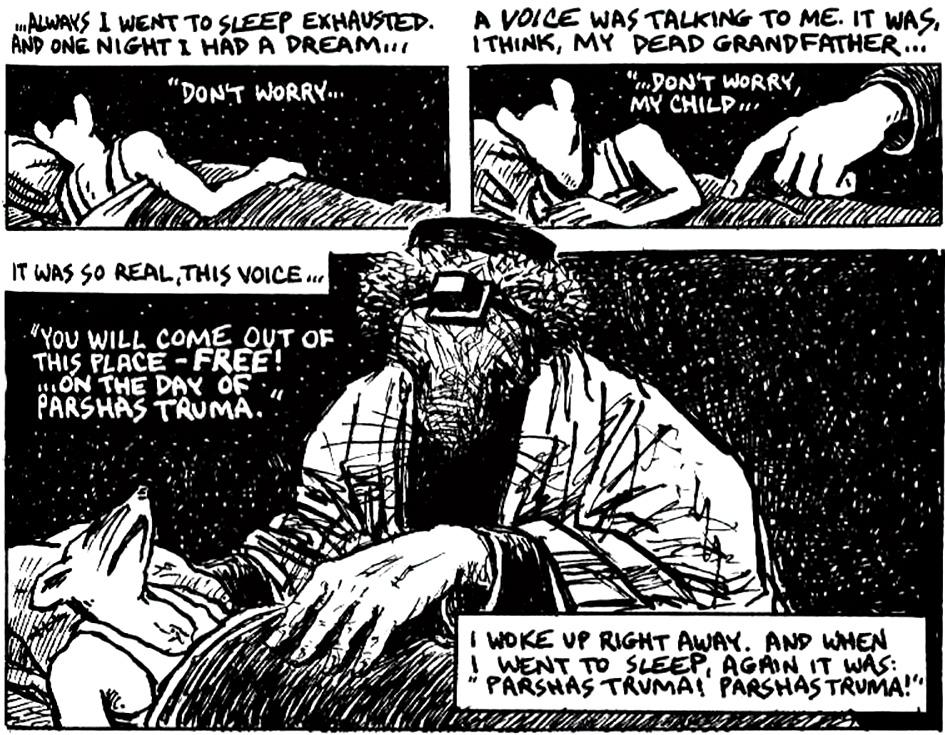

Art Spiegelman's Maus, a biographical strip based on his father’s imprisonment at Auschwitz.

From Codex to Comix: A Cartoon History of Comics

110 CE.

Roman emperor Trajan erects massive column to celebrate victory over the Dacians. Spiral frieze depicts the military campaign in 155 sequential scenes, from Trajan crossing the Danube to the death of the Dacian King Decebalus.

600-900.

Mayan scribes use “speech scrolls,” ancestors of the speech bubble, to indicate dialog.

History of a Coat, by William Heath

1500s.

Aztec priests create codices, pictorial “strips” depicting legends, rulers, conquests, and ceremonies. Scholars have identified some 500 surviving codices; many of those from the Colonial era include captions and commentary.

1734.

Artist William Hogarth paints A Rake’s Progress, a sequence of eight scenes depicting the decline and fall of a dashing playboy who squanders his fortune on gambling, liquor, and vice.

1826.

Glasgow Looking Glass runs History of a Coat, by William Heath, a comic strip complete with panels, speech bubbles, and a cliff-hanger.

1897.

The irrepressible Katzenjammer Kids make their debut in the New York Journal, complete with outsized pranks and outrageous German accents.

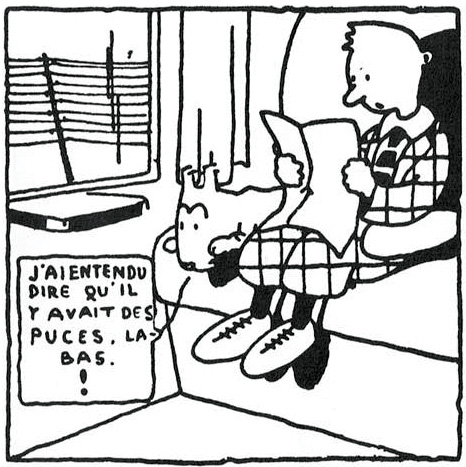

Hergé writes the first Adventures of Tintin

1929.

Hergé writes the first Adventures of Tintin. Dell Comic publishes The Funnies #1, the first American newsstand comic.

1938.

DC Comics publishes Action Comics #1, featuring the buttoned-down reporter Clark Kent, whose secret identity is... Superman! The Man of Steel ignites the superhero genre. DC soon unleashes Batman, Wonder Woman, the Flash, Green Lantern, the Atom, Hawkman, Green Arrow, and Aquaman.

WWII.

American GIs share their comic books with civilians in Europe and Japan, cross-pollinating those countries’ own graphic traditions.

Sazae-san, by Machiko Hasegawa

1946.

First installment of Sazae-san, by Machiko Hasegawa, a comic strip based on a “liberated” Japanese woman, ushers in the birth of manga.

Late 1940s.

Comics become a thriving business in the US as returning GIs seek more mature content and titles get more lurid.

1954.

Psychiatrist Fredric Wertham warns that comic books are leading a generation of American kids into juvenile delinquency. Senate launches a probe into the industry. Publishers adopt the Comics Code, forswearing “lurid, unsavory gruesome illustrations,” excessive violence, illicit sex, crooked cops, and sympathetic criminals, and promising that good will always triumph over evil—on the page, at least.

Late 1950s.

The Code puts several publishers out of business and forces others to sand down their storylines. What good is superhuman strength if you can’t punch bad guys? Violence is permitted against monsters, however, so superheroes are increasingly pitted against aliens and supervillains, which robs the genre of its social relevance.

1960.

DC Comics revives the superhero genre with the Justice League of America—Batman, Aquaman, the Flash, Green Lantern, Martian Manhunter, Superman, and Wonder Woman.

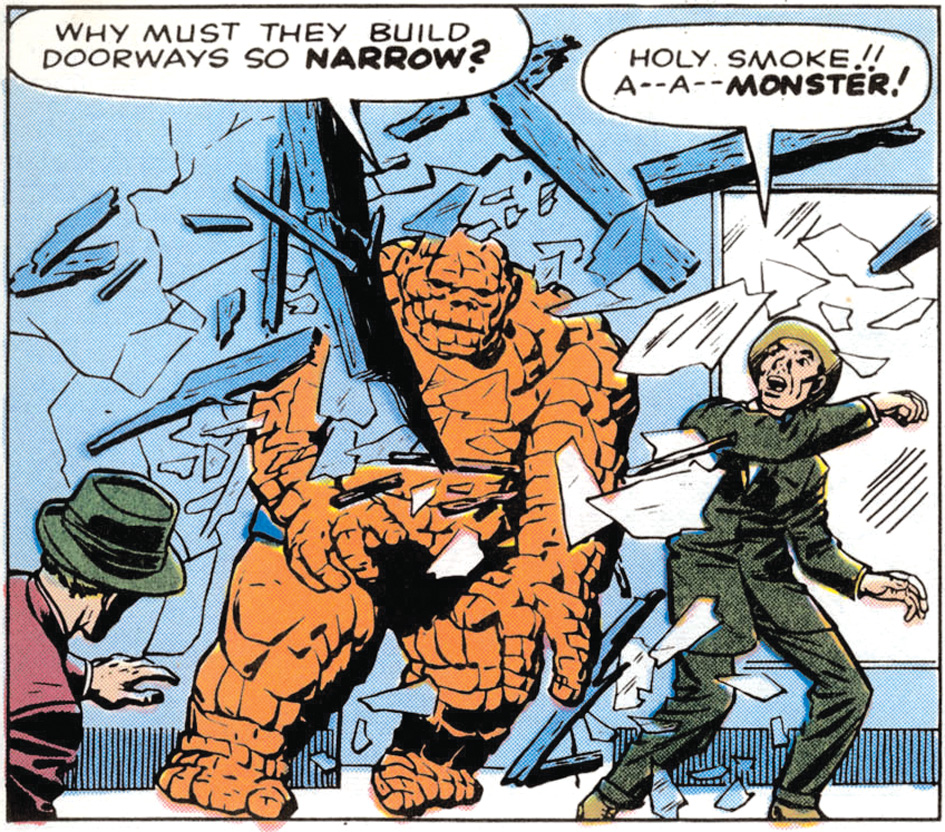

Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four

1961.

At Marvel, writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby are given the task of going toe to toe with the Justice League. Instead of flawless paladins, they create a team of conflicted characters with complex relationships—the Fantastic Four.

1968.

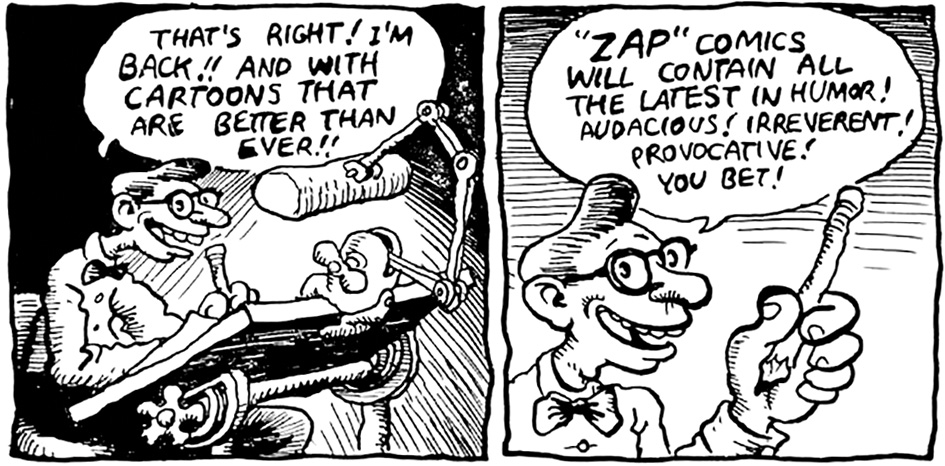

R. Crumb publishes Zap Comix, a signal event for the underground comix movement, which defy the Code and revel in counterculture themes such as sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.

R. Crumb publishes Zap Comix

1980.

Art Spiegelman publishes first installment of Maus, a biographical strip based on his father’s imprisonment at Auschwitz.

1981.

Frank Miller takes over Marvel’s Daredevil, giving the blind crimefighter a darker past and a mean streak. Sales soar.

1991.

First appearance of Naoko Takeuchi’s Sailor Moon, featuring independent female characters with magical powers. Global sensation.

Tags: Academics, Professors, Students, Cool Projects