Showrunner

How playwright Eric Overmeyer '73 mastered the small screen.

Establishing shot: outdoors. Nighttime. A palm tree waves in a light wind. Two homicide detectives sit in an unmarked car beside a chainlink fence. Stadium lights illuminate an overcast sky. On a stakeout in gritty LA, the two men exchange small talk about the ball game and the weather.

“Won’t go nine,” our protagonist, Harry Bosch, says. “What are you all of a sudden, an amateur meteorologist now?” his partner quips. Finally their mark exits his family home and the two detectives follow, first by car, then Bosch trails on foot. Before long, just as Bosch predicted, a drenching rain begins to fall, and he finds himself following the suspect down a dark alley where at last he confronts him. Bosch draws his gun. “Manos!” he yells. The man seems to cooperate, but then, he reaches down. “Freeze!” Bosch says and points his gun. The man reaches into his pocket and Bosch squeezes the trigger.

Bosch, based on the bestselling mystery series by Michael Connelly, was developed for television by Eric Overmyer ’73 and has quickly become one of Amazon’s most popular original series. The pilot was picked up by Amazon Studios’ crowdsourced selection process, and the show became the very first Amazon Original to be commissioned for a second season. Bosch is an addictive, quintessential police procedural that follows case-hardened LAPD homicide detective Hieronymous “Harry” Bosch—named for the medieval Dutch painter whose famous depiction of heaven and hell serves as a metaphor for LA—as he investigates a case that hits uncomfortably close to home.

But far from the palm trees of LA and the glamor of Hollywood, Overmyer, the series’ writer and show-runner, got his start in a very different world: doing experimental theatre in the Pacific Northwest. It was a surprising twist: that the Reed student buying dog-eared scripts at Powell’s with money he raised from collecting bottles and cans, who devoted himself to avant-garde theatre by sitting half-naked in a trash can for an evening, or filming a silent, 8-millimeter version of Waiting for Godot wearing a bowler hat in a cow field, would later become the award-winning screenwriter behind hit television shows like The Wire and Tremé.

“We’re talking 30-some years ago,” he said in a recent conversation with Reed. “Portland wasn’t the bright shiny city it is now. It was a little mossy, not very diverse. Lumberjacks and fishermen.” Still, it was a place that was receptive to experiment—good and bad.

At Reed he immersed himself in a wide variety of productions, from classical to absurdist. His freshman year, he appeared in Machiavelli’s Mandragola, played Gogo in a thesis production of Waiting for Godot staged by Chris Steele ’75, followed by Endgame, directed by Prof. Roger Porter [1961-]. He was in a thesis production of Pinter’s Landscape and Silence, and with Lee Blessing ’71 did an adaptation of Mrozek’s absurd, macabre comedy, Out at Sea, in the old Student Union. Senior year he directed Robert Montgomery’s Subject to Fits.

Busy acting and directing, he had not considered writing for theatre; instead, he wanted to be a poet. But, his thesis adviser, Prof. Larry Oliver [1972-77] introduced a playwriting course, and Overmyer seized an opportunity to write and direct a play called A Clam’s Chance on Mt. Everest. Overmyer describes the play as “a mess,” but after he graduated, Oliver encouraged him further by commissioning work: a draft of what Overmyer calls his “first real play,” Native Speech, which was produced at Reed. In a 1995 commencement address Overmyer said, “it was at Reed, and largely because of Reed and the people that I met there, that I slowly began to think of myself as a writer and an artist.”

Portland boasted a lively theatre scene in the 1970s and early 1980s and Overmyer plunged into it. “The most important theatre in Portland was the Storefront Theatre,” he says. “It did a lot of original work, as well as plays that had been done elsewhere; it was very visual. I was lucky to do a little work there.” He directed plays by Shepard and Beckett, Mamet and Wilde. Portland theatre created a work ethic among its members: “The overriding factor in those days was money – the utter lack of it,” he remembers. “Fortunately, it was possible to find affordable space in out-of-the-way places to do theatre. And the lack of money spurred a lot of marvelous invention. Necessity being the mother of all that.”

In short order, he became one of Portland’s brightest stars, winning a Drammy award (then called the Willies) for the 1978-79 season as best supporting actor in Shepard’s The Tooth of Crime. But soon he left Portland for New York.

Overmyer has written around 10 plays. On the Verge, or the Geography of Yearning, his most-produced play, is a respected comedy about three Victorian explorers, noted for its ambitious word play and praised in the New York Times as a script that “has legs.” “If New York is fortunate, it may become one of Mr. Overmyer’s ports of call,” the reviewer said, and for a while it did: Overmyer’s plays opened in venues off Broadway in the 1980s and 90s. His work as a playwright demonstrates an abiding interest in language and genre, drawing comparisons to Stoppard, Pynchon, and T.C. Boyle. This period saw the openings of his plays Amphitryon, the noirish Dark Rapture, and Mi Vida Loca. In 1989 he opened In A Pig’s Valise, a hard-boiled detective story and musical comedy that featured pop band Kid Creole and the Coconuts. Overmyer told the New York Times, “I was drawn to the detective form because it’s so American. The piece is really about American vernacular, both linguistic and musical.”

At this time he was also a jobbing screenwriter. His first credits include a handful of scripts for the medical drama St. Elsewhere in 1985-86. He worked on sitcoms, among them the cult favorite The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd, as well as thrillers (The Cosby Mysteries) and adaptations, including the short-lived series The Big Easy. In 1994, the New York Times noted that Overmyer kept “his careers compartmentalized. The linguistic ornamentation that distinguishes his own plays is absent from his television work.”

And yet, Overmyer’s experiments with language and genre would prove to be key to his transition from theatre to screen. “A little language goes a long way when you’re writing for the camera,” he says, adding that his theatre background helped him “enormously” in writing for TV. “I know how actors work, I know how to write characters. I had to learn how to be succinct and how to shape scenes in a different way. I still don’t think visually well enough to be a genuine screenwriter—it’s dialogue I’m interested in, and how character is revealed through it.”

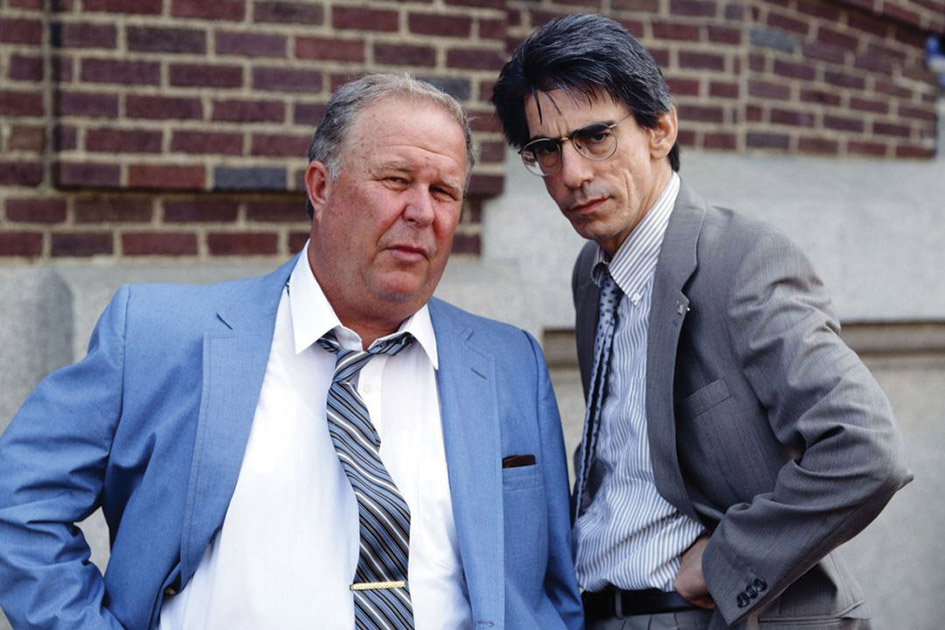

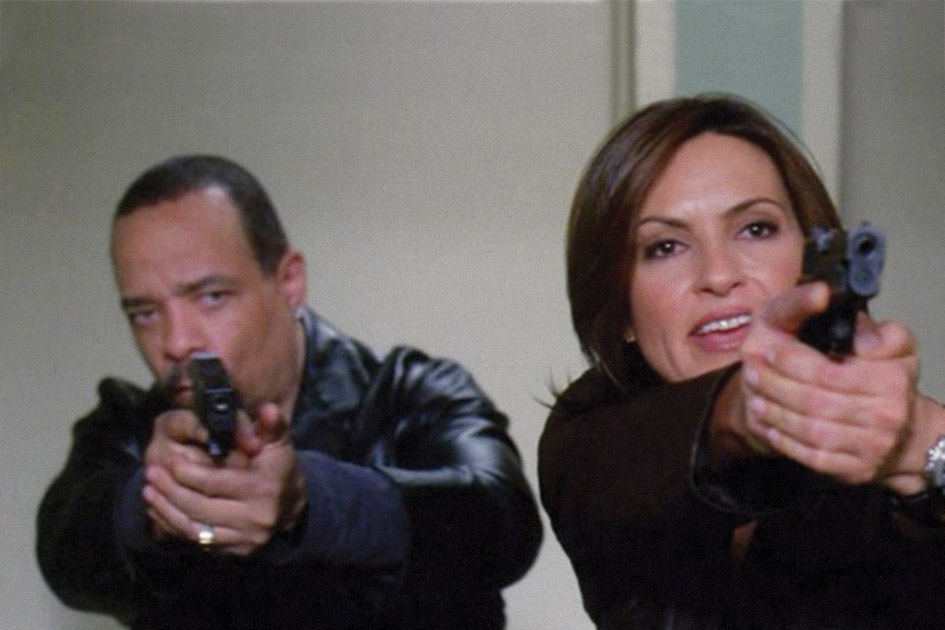

Overmyer’s career took off in 1996, when he began to work on Homicide: Life on the Street, a smart TV police procedural based on the book by Baltimore reporter David Simon. Overmyer wrote several episodes and acted as a producer on the program, which won an array of Television Critics Association Awards, and is frequently included in “Best TV Shows of All Time” lists. The show was known for departing from network conventions and advice: focusing on more than one homicide, eschewing happy endings, and allowing for plot complications like unsolved cases. Other work on crime dramas followed. Overmyer worked on Law and Order and Law and Order: Special Victims Unit in the early 2000s, before joining up again with Simon, who had a new hit show: The Wire.

By 2006 television was in the thick of a transformation from the much-derided network fare that had dominated the medium for decades into a new golden age, made possible by cable channels such as HBO which were backing series with interesting, complicated narratives that stretched out over entire seasons. These were shows that explored darker territory than television of the past, and whose cliff-hangers were not simply questions of plot, but investigations of character. Six-Feet Under had just concluded, The Sopranos was wrapping up, and shows like Breaking Bad and Mad Men were on the horizon. Even comedies like Sex and the City had become character-driven stories with anti-heroes who changed over the course of the series. These shows were in the vanguard of a revolution in media—how viewers consumed television was shifting. DVDs and streaming made binge-watching a national pastime. Soon, Netflix and Amazon would be producing original content and entire seasons would be released all at once. Commercial breaks were no longer the organizing principle for plot climaxes and resolutions. Televisions themselves changed; the TV in your living room could accommodate more nuanced visual storytelling and cinematography.

The Wire was a police procedural set in Baltimore, but was fundamentally unlike any network cop show that had preceded it. In a pitch to HBO executives, Simon wrote that The Wire would “ultimately bring viewers from wondering, in cop-show expectation, whether the bad guys will get caught, to wondering instead who the bad guys are and whether catching them means anything at all.” Overmyer joined the writing room for the show’s fourth season, for which he won a Writers Guild of America Award in 2008 and an Edgar Award in 2009. “The Wire is a beautiful, brave series. This is its best season yet,” the New York Times raved.

Overmyer and Simon went on to create Tremé, another critically acclaimed HBO drama known for its realistic depiction of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina. The pursuit of authenticity brought the show’s creators together with a fascinating denizen of the New Orleans music scene: Reed alumnus Davis Rogan ’90, who is the basis of the lead character Davis McClary. In Tremé, many of Overmyer’s interests came together: music, genre, the American vernacular, and New Orleans, where he lives part-time. Tremé is known for taking artistic license with its structure and pacing, lingering on setting, character, and music. In a glowing review, Robert Lloyd, television critic for the Los Angeles Times, lauded it as “perhaps the only show on television in which characters’ colors and cultures are not incidental to their gifts and predicaments, their advantages or obstacles.” It’s “not a plot-driven entertainment but moving and various and messy,” he says. “In my more perfect universe, it would be the cable drama everyone talks about and other shows want to imitate.”

Most recently, Overmyer is at work on the movie New Orleans, je t’aime, a series called Capitol Crimes, and Bosch, which has just been picked up for a third season by Amazon. As a playwright, Overmyer was drawn to outcasts exploring challenging terrain and using their words or language as tools to cope with reality, from his trio of Victorian explorers in On the Verge, to his take on Peer Gynt, set in the Pacific Northwest. In his work for screen, we see these same preoccupations, and he’s in good company. If Mad Men, House of Cards, Breaking Bad, and the Sopranos have shown us anything, it is that audiences are hungry for nuanced stories and complicated protagonists coping with an often gritty, urban American reality.

Exterior. Night. Rain falls and Bosch stands over the body of the man he has just killed, his gun still drawn. His partner drives up, and the two men make troubled eye-contact; Bosch is illuminated in the unforgiving glare of the police car’s headlights. Soon after, the police chief arrives, a tall, imposing figure with a deep voice. “In God’s name, Bosch, another one?” he says. And so the series begins. Roll the opening credits.

Tags: Alumni, Awards & Achievements, Books, Film, Music, Performing Arts