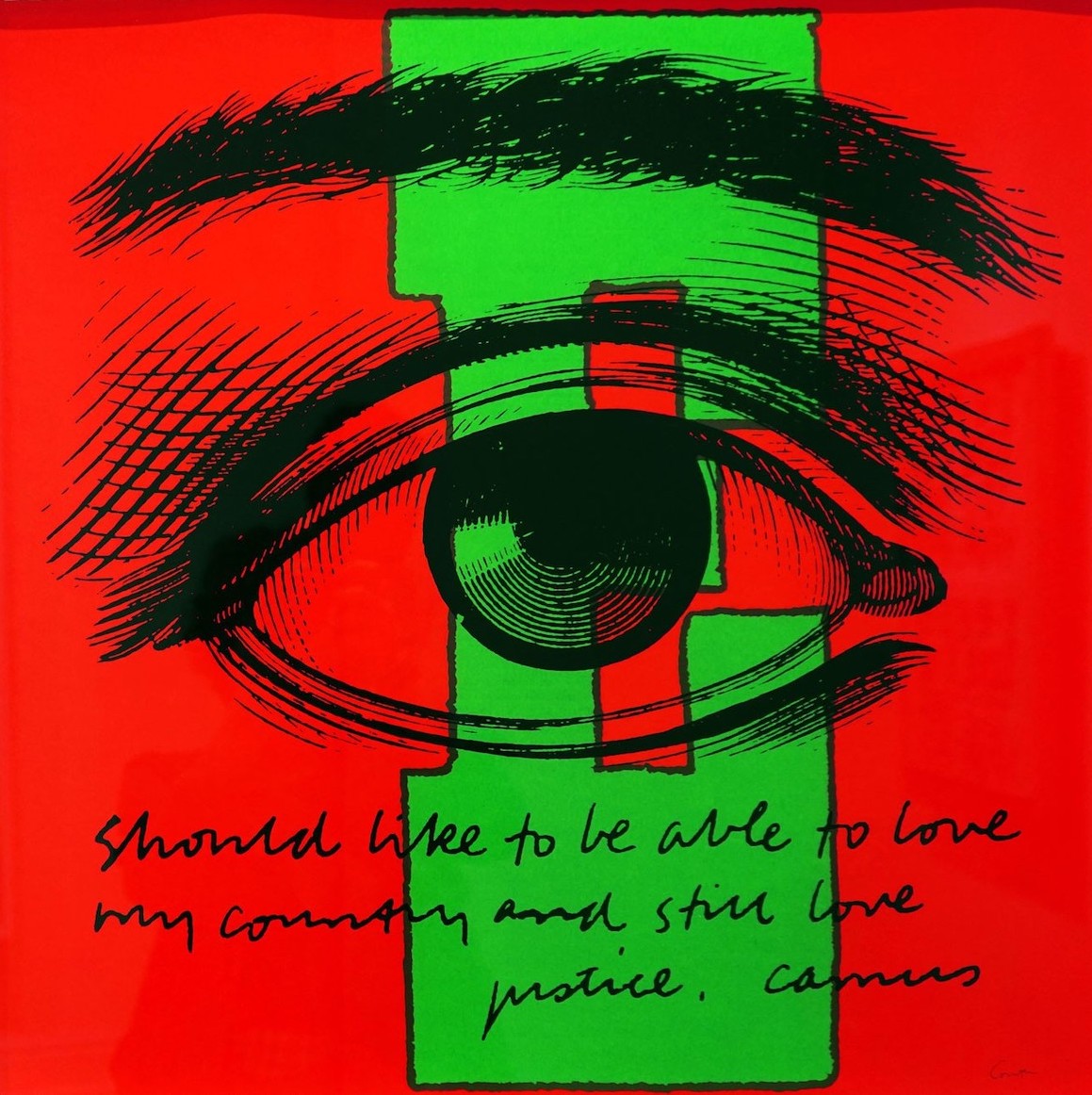

Sister Mary Corita Kent, e eye love, ca. 1968. Serigraph, 22.75 x 22.75 in. Text reads: “[I] should like to be able to love my country and still love justice. Camus”

Give Me the Message! Political posters from Cuba, France, and the United States, 1960–75

Image Gallery Exhibition FileNovember 1 - December 15, 2019

Give Me the Message! presents three bodies of original posters created between 1960 and 1975 in three different parts of the world: Cuba, France, and the United States. Together they offer collective and individual perspectives on the Communist revolution in Cuba; Vietnam War opposition and religious activism in the United States; and the student uprisings in Paris in May, 1968.

Tuesday, November 5, 4:30—7:00 pm, Public Reception at the Cooley Gallery

On view Friday, November 1—Sunday, December 15, 2019

The gallery is open every day, Tuesday through Sunday, 12:00—5:00 pm. Free and open to the public.

Poster artists in Communist Cuba had many inspiring exemplars: Russian and Soviet propaganda, Latin American modern art, and Chicano art and pop art from the United States. The Cuban government established a central arts agency—the Organización de Solidaridad con los Pueblos de Asia, África y América Latina, or OSPAAAL—and educated and employed the most talented artists in the country.

The original lithographs on display are OSPAAAL posters from the 1960s and ’70s—the most celebrated era of Cuban poster design. During this time, individual artists were credited for their work and held public exhibitions of their posters and paintings.

In keeping with OSPAAAL’s mission to advance global solidarity, many of the posters venerate Communist leaders and revolutionary struggles. On view are such iconic works as Richard Nixon Vampire (1972) and US Techno-Drone Soldier (1971), both by Alfredo Rostgaard; and Elena Serrano’s Day of the Heroic Guerrilla (1968). All Cuban works in the exhibition were generously loaned by Matthew P. Bergman ’86.

Corita Kent (1918–86) was an artist, educator, and social justice advocate. She entered the order of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles at the age of eighteen. Eventually, she taught in the art department at Immaculate Heart College, and in 1964, she became its director. There, she developed experimental teaching methods.

Corita saw Andy Warhol’s infamous Campbell’s Soup Cans exhibition at LA’s Ferus Gallery in 1962. She admired pop art’s mash-up of advertising imagery, slogans, and bold colors. During the ’60s Corita’s work became more political, overtly denouncing the war in Vietnam as well as racism and injustice in the United States.

In 1968 Corita left her order and continued making art. She engaged in social and religious activism until her death in 1986, by which time she had created thousands of serigraphs, watercolors, and public and private commissions. The Reed College Art Collection contains over two hundred works by Corita Kent, a generous gift by an anonymous donor.

Paris, France. May 1968. Thousands of silk-screened posters such as these covered the façade of the Sorbonne and its surrounding streets as students, workers, and everyday people banded together to fight police brutality and oppression under the government of President Charles de Gaulle. By mid-May, people marched in the millions. The silkscreens were made by the Atelier Populaire, a collective of art students and striking workers who occupied the École des Beaux-Arts on May 14, working around the clock in shifts to provide the massive uprising with a visual voice. They printed several thousand posters each day and installed them at night.

Poster designs were submitted anonymously within the group and reviewed in meetings; once complete, they were “signed” with a simple rubber stamp marking their origin. Though de Gaulle ultimately remained in power, the posters transmit the passion, energy, and political agenda of May ’68—a critical moment in French history that had lasting repercussions. The Atelier Populaire posters are part of the Reed College Art Collection.