Adolfson Associates, Inc. 2001. Crystal Springs Creek Fish and Wildlife Habitat Assessment. Prepared for the City of Portland www.reed.edu/canyon

American Forests. 2001. Regional Ecosystem Analysis for the Willamette/Lower Columbia Region of Northwestern Oregon and Southwestern Washington State: Calculating the Value of Nature. American Forests Report.

Audubon Society of Portland. 2008. 2007-2008 Annual Report.

Bell, J.F., J.S. Wilson, and G.C. Liu. 2008. Neighborhood Greenness and 2-year changes in Body Mass Index of Children and Youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35(6) 547-553.

Bin, Okmyung. 2005. A semiparametric hedonic model for valuing wetlands. Applied Economics Letters 12: 597-601.

Bockstael, Nancy E., A. Myrick Freeman, III, Raymond J. Kopp, Paul R. Portney, and V. Kerry Smith. 2000. On Measuring Economic Values for Nature. Environmental Science & Technology 34(8): 1384-1389.

Bowker, J.M., John C. Bergstrom, Joshua Gill, and Ursula Lemanski. 2004. The Washington & Old Dominion Trail: An Assessment of User Demographics, Preferences, and Economics. Final Report Prepared for the Virginia Department of Conservations (December 9).

Brander, L.M. and M.J. Koetse. 2007. The Value of Open Space: Meta-Analyses of Contingent Valuation and Hedonic Pricing Results. Institute for Environmental Studies Working Paper (December).

Breffle, William S., Edward R. Morey and Tymon S. Lodder. 1998. Using Contingent Valuation to Estimate a Neighbourhood's Willingness to Pay to Preserve Undeveloped Urban Land Urban Studies 35(4) 715-727.

Bureau of Environmental Services. 2008. Invasive Plants Strategy Report. Prepared

for the City of Portland

Bureau of Environmental Services. 2009. Crystal Springs Creek Habitat Restoration Projects. Prepared for the City of Portland.

Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. 1991. Portland: Johnson Creek Basin protection plan. City of Portland, Oregon. Cited by Reed College Canyon.

Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. 2009. Quarter Section Maps: Southeast Quarter Sections. Maps 3633 & 3634, http://www.portlandonline.com/bps/

index.cfm?c=34112& (accessed December 4, 2009).

Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. 2009. Zone Summaries: Overlay Zones. City of Portland, Oregon. http://www.portlandonline.com/bps/index.cfm? a=64465&c=36238 (accessed December 4, 2009).

Chattopadhyay, Sudip. 1999. Estimating the Demand for Air Quality: New Evidence Based on the Chicago Housing Market Land Economics 75(1) 22-38.

Champ, P.A., K. J. Boyle and T.C. Brown. 2003. A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Cusack, Chris, Michael Harte, and Samuel Chan. 2009. The Economics of Invasive Species. Prepared for the Oregon Invasive Species Council.

DeGroot, Rudolf S., Matthew A. Wilson and Roelof M. J. Boumans. 2002. A Typology

for the Classification, Description and Valuation of Ecosystem Functions, Goods and Services Ecological Economics 41(3) 393-408.

Eshet, Tzipi, Mira G. Baron, and Mordechai Shechter. 2006. Exploring Benefit Transfer: Disamenities of Waste Transfer Stations Environmental and Resource Economics 37(3) 521-547.

ECONorthwest. 2004. Comparative Valuation of Ecosystem Services: Lents Project Case Study. Rep. Eugene: ECONorthwest, 2004. Print.

ECONorthwest. 2009. Economic Arguments for Protecting the Natural Resources of the East Buttes Area in Southeast Portland. Prepared for the Bureau of Environmental Services.

Entrix. 2009. Ecosystem Benefits of the Grey to Green Initiative [Draft]. November 6. Report prepared for City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services.

EPA. 2009. EPA Finds Greenhouse Gases Pose Threat to Public Health, Welfare. Proposed Finding Comes in Response to 2007 Supreme Court Ruling. 04/17/2009. View website

Evans, Mark (ed.) 2004. Policy Transfer in Global Perspective Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing.

Gorsevki, Taha, Quattrochi, and Luval. 2002. Air Pollution Prevention Through Urban Heat Island Mitigation: An Update on the Urban Heat Island Pilot Project. Draft report, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley.

Helvoigt, Ted L. and Claire A. Montgomery. 2003. Trends in Oregonians’ Willingness to Pay for Salmon. Corvallis, Oregon, Oregon State University: Working Paper.

Hennings, Lori. 2006. State of the Watersheds monitoring report. Metro Regional Government, Oregon.

Hennings, Lori. 2009. State of the Watersheds 2008. Metro Regional Government, Oregon. View website (accessed November 27, 2009).

Henry W.A. (ed.) 1993. The Dictionary of Ecology and Environmental Science Pownal, Vermont, Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

Hillsdon, M., J. Panter, C. Foster, and A. Jones. 2006. The Relationship between Access and Quality of Urban Green Space with Population Physical Activity Public Health 120(12) 1127-1132.

Kaplan, S. 1995. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward and Integrative Framework Journal of Environmental Psychology 15(3) 169-182.

La Rouche, Genevieve. 2003. Birding in the United States: a demographic and economic analysis. Division of Federal Aid, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Layton, David F. and Richard A. Levine. 2003. How Much Does the Far Future Matter? A Hierarchical Bayesian Analysis of the Public’s Willingness to Mitigate Ecological Impacts of Climate Change Journal of the American Statistical Association 98 (463) 533-544.

Lee, Karl K. and Daniel T. Snyder. 2009. Hydrology of the Johnson Creek Basin, Oregon. United States Geological Survey. Scientific Investigations Report 2009-5123.

Lutzenhiser, Margot and Noelwah R. Netusil. 2001. The Effect of Open Spaces on a Home’s Sale Price Contemporary Economic Policy 19(3) 291-298.

Mahan, Brent L., Stephen Polasky, and Richard M. Adams. 2000. Valuing Urban Wetlands: A Property Price Approach. Land Economics 76 (1): 100-113.

Metro. 1995 natural areas bond measure. Portland, OR. View website (accessed December 8, 2009).

Metro. 2009. Region's voters direct Metro to purchase natural areas. Portland, OR. View website (accessed December 8, 2009)

Metro. 2009. Metro Council releases updated 20- and 50-year population, employment forecasts. Portland, OR. View website (accessed December 13, 2009)

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2003. Recreation section

Mufson, Steven and Fahrenthold, David A. “EPA is preparing to regulate emissions in Congress’ stead.” The Washington Post.” 12/08/2009. View website

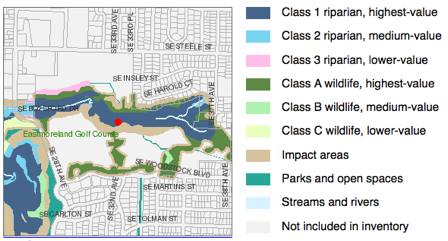

Netusil, Noelwah. 2006. Economic Valuation of Riparian Corridors and Upland

Wildlife Habitat in an Urban Watershed. Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education 134 (July): 39-45.

Novak, David and Crane, Daniel E. and Stevens, Jack C. 2006. Air pollution removal by urban trees and shrubs in the United States. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 4 (3-4) 115-123

Office of Protected Resources. Coho Salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries Service. View website (accessed December 3, 2009).

Oregon Department of Agriculture. 2000. Economic analysis of containment programs, damages, and production losses from noxious weeds in Oregon.

Oregon Department of Conservation and Development. Goal Adoption and Amendment Dates. State of Oregon. View website (accessed December 3, 2009).

Oregon Department of Conservation and Development. 1974, amend. 1996. Goal 5: Open Spaces, Scenic and Historic Areas, and Natural Resources. State of Oregon. View website (accessed December 3, 2009).

Oregon Department of Conservation and Development. 1974. Goal 6: Air, Water and Land Resources Quality. State of Oregon. View website

Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. 2003. 2003-2007 Oregon Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan. View website

Palmes, E.D., Gunnison, A.F., DiMattio, J., 1976. sampler for nitrogen dioxide. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 37: 570-577.

Pettis, John. 2008. Title 13 / Model Ordinance White Paper. City of Gresham, Oregon. View website (accessed December 23, 2009).

Pimentel, David, Christa Wilson, Christine McCullum, Rachel Huang, Paulette Dwen, Jessica Flack, Quynh Tran, Tamara Saltman, and Barbara Cliff. 1997. Economic and environmental effects of biodiversity. Bioscience 47: 747-757.

Poor, Joan P., Keri L. Pessagno, and Robert W. Paul. 2006. Exploring the hedonic value of ambient water quality: A local watershed-based study. Ecological Economics 60: 797-806.

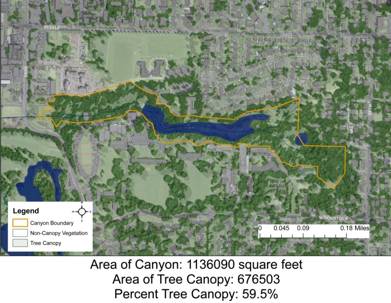

Portland Parks and Recreation. 2007. Urban Tree Canopy Report. Recreation section.

Reed College Canyon Homepage. View website (accessed December 3, 2009).

Reed College Canyon. Natural History of the Canyon: Canyon Plants. View website (accessed December 3, 2009).

Reed College News Center. 2007. Reed College Acquires Former Rivelli Farm Property.

Richardson, Leslie and John Loomis. 2009. The total economic value of threatened, endangered, and rare Species: an updated meta-analysis. Ecological Economics 68:1535-1548.

Rosenthal, Elisabeth. “Climate Talks Near Deal to Save Forests.” NY Times: Environment. 12/15/2009. View website

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. 2009. Forest resilience, biodiversity, and climate change: a synthesis of the biodiversity/resilience stability relationship in forest ecosystems. Series No. 43.

Stathopoulou, Mihalakakou, Santamouris, and Bagiorgas. 2008. On the impact of temperature on tropospheric ozone concentration levels in urban environments Journal of Earth System Science 117(3) 227-236.

Streiner, Carol and John Loomis. 1996. Estimating the Benefits of Urban Stream Restoration Using the Hedonic Price Method Rivers 5 (4) 267-78.

Ulrich, R.S. 1981. Natural Versus Urban Scenes Environment and Behavior 13(5) 523-556.

Ulrich, R.S. 1984. View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery Science 224(4647) 420-421.

United Nations. 2007. UNFPA State of World Population 2007: Unleashing the Potential of Urban Growth. View website

U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. State and County Quick Facts. View website

Woodward, Richard and Yong-Suhk Wui. 2001. The economic value of wetland services: a meta-analysis. Ecological Economics 37: 257-270.

Zabel, Z.E. and K.A.Kiel. 2000. Estimating the Demand for Air Quality in Four U.S. Cities Land Economics 76(2) 174-194.