Ceratioid Anglerfish Mating: Sexual Dimorphism and Parasitism

| Home |

| Mechanism |

| Ontogeny |

| Phylogeny |

| Adaptive Value |

| References |

Mechanism

How do anglerfish find mates?

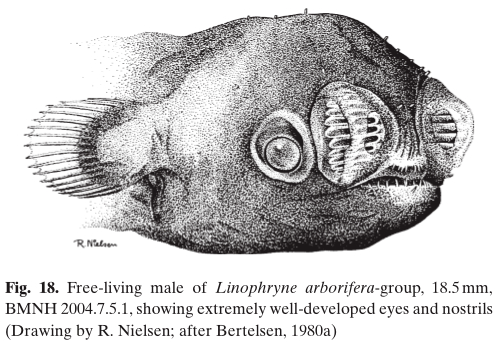

It has long been believed that anglerfish use a combination of both olfactory and visual cues to seek out and identify members of the opposite sex. This idea was supported most directly by early researchers' observations that the eyes and nostrils of free-living males are typically large and well-developed, and that they degenerate rapidly with the onset of parasitic attachment. According to this theory, the males use their large and sensitive nostrils and eyes to pick up upon conspecific female olfactory and visual cues such as pheremones and bioluminescent lures (Bertelsen 1951).

It has long been believed that anglerfish use a combination of both olfactory and visual cues to seek out and identify members of the opposite sex. This idea was supported most directly by early researchers' observations that the eyes and nostrils of free-living males are typically large and well-developed, and that they degenerate rapidly with the onset of parasitic attachment. According to this theory, the males use their large and sensitive nostrils and eyes to pick up upon conspecific female olfactory and visual cues such as pheremones and bioluminescent lures (Bertelsen 1951).

While current evidence still generally supports this idea, more recent research has suggested that many species may rely primarily on either vision or smell, and not both. This distinction is noted upon observing free-living males of certain species which have either well-developed eyes and reduced nostrils or well-developed nostrils and reduced eyes, but not both (Pietsch 2005).

Parasitism

Upon locating a con-specific female, free-living male anglerfish bite onto their mate's body. With time, the epidermal tissue of the male fuses with that of the female and their circulatory systems unite, although the exact mechanism through which fusion is mediated is unknown. The male becomes an obligate parasite and survives by receiving nutrients directly from its mate; the female essentially becomes a self-fertilizing hermaphroditic host to the male, whose internal organs deteriorate but whose testes remain enlarged and functional (Pietsch 1975). Following the onset of parasitism, the male skin also changes, becoming darker and spiny (Pietsch 1976).

Upon locating a con-specific female, free-living male anglerfish bite onto their mate's body. With time, the epidermal tissue of the male fuses with that of the female and their circulatory systems unite, although the exact mechanism through which fusion is mediated is unknown. The male becomes an obligate parasite and survives by receiving nutrients directly from its mate; the female essentially becomes a self-fertilizing hermaphroditic host to the male, whose internal organs deteriorate but whose testes remain enlarged and functional (Pietsch 1975). Following the onset of parasitism, the male skin also changes, becoming darker and spiny (Pietsch 1976).

In anglerfish with obligate reproductive parasitism (Creatiidae, Linophrynidae, and Neoceratiidae families), reproduction can only occur after the male has fused with the female. Interestingly, after metamorphosis, the free-living males become not only dependent on the females for reproduction, but also for surival: adapted solely for parasitism, their jaws are incapable of capturing prey, and their alimentary canal is undeveloped, "indicating that the males do not feed after metamorphosis and thus are fully dependent on a parasitic association with a female for long-term survival" (Pietsch 2005).

Lauren Carley, Jessie Ellington, Michael Turvey. 2010.