Shades of White

Curated by June Black

Catalog (pdf)

Work in Exhibition

32 Steel Boxes with Silk Panels Boxes. Boxes range from 4” x 20” to 10” x 30” Mild steel, 18-gauge, bent, welded, buffed and coated with matte finish; 100% silk from Uzbekistan and China, natural dyes.

Artist’s Statement

Shades of White, an installation created for the Artist Project Space at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, is the result of years of research. The work represents the “Gates Skin Color Chart,” a tool used by geneticists and anthropologists in the mid-20th century for racial classification. It is based on the research of Dr. Alexandra Minna Stern, a medical historian at the University of Michigan. Stern researches the history of eugenics and its attendant genetic and racial discrimination as practiced in the United States from 1900-87.

Stern’s books, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (2005) and Telling Genes: The Story of Genetic Counseling in America (2012), explore racially discriminatory practices—such as the forced sterilization of individuals supported at the public’s expense, including children in orphanages, patients in mental health facilities, and prisoners—in the United States (and in the American West, especially). I felt it was important to create a work that would make these events visually accessible. Just as Stern’s work exposes the deeply problematic charting of physical and mental anomalies and skin color by medical professionals in her books, this installation visually critiques the results of eugenics. I reproduced the “Gates Skin Color Chart,” a tool created by geneticists at the University of Michigan that attempted to typologize race by color, with labels ranging from “African” to “Caucasian”. These charts had practical and material effects, as they were used to determine the adoptability of children in the care of the state. These inequitable practices haunt us today. In fact, it was not until 2002 that Governor Kitzhaber asked forgiveness from the victims of discriminatory sterilization in Oregon’s orphanages and other state institutions.

Although I have done similar genetic research-based projects, I have not previously taken on such controversial material. This project exposes the genetic discrimination at play in the United States beginning in 1900 and links it to the practice of eugenics aimed at achieving racial hygiene in Nazi Germany. As Stern points out in Eugenic Nation, the top eugenicists in the U. S. collaborated with and followed the same practices as their Nazi counterparts in 1930s Germany. In fact, the “Gates Skin Color Chart” is based on a similar chart dating to 1905, created by Felix von Luschan, which the German Society for Racial Hygiene utilized in selecting the victims of the forced sterilizations performed in that country.

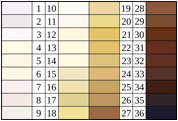

Felix von Luschan's Chromatic Scale (pictured above) was used to establish racial classifications of populations according to skin color. Named for its inventor, Felix von Luschan, the equipment consisted of thirty-six opaque glass tiles that were compared to the subject's skin, ideally in a place that would not be exposed to the sun regularly, such as the underarm. Source: Institut für Kulturgeschichte der Antike der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Institut für Klassische Archäologie der Universität Wien.

- Ruggles Gates, created a skin color chart used from the 1940-60 to determine the racial identity of newborns at American medical instructions and adoption agencies. His chart consisted of nine squares ranging from dark to white skin tones. Then, using a more sophisticated method of skin color determination, he created his own version in the late 1950s to be used by American medical and adoption agencies.4

Using organic natural dyes on a variety of silks, Shades of White recreates the genetics of skin color as determined by melanin. The work is a very direct critique of the von Luschan’s and Gates’ skin color charts as determinist systems of measure. Although we use the words black and white to describe human skin color (and people), no one is actually black or white. The pigmentation that makes up our skin color comes from our genetic heritage and the geographic location of our ancestors, which gives each of us various types and levels of melanin.

The melanocortin 1 receptor gene (MC1R) is primarily responsible for determining whether pheomelanin and/or eumelanin is produced in the human body. Pheomelanin produces the light skin values, which are reds, pinks, yellows, and blues.

Eumelanin, which produces the darker skin values, is a blend of black, brown, and red. Because so many of us represent a mixture of ethnic backgrounds, it is not uncommon for individuals to have a blend of both pheomelanin and eumelanin. This work is meant to point out the astonishing variety of “shades” that comprise each of us and to point to the fact that no one is pure white or pure black—we are all a spectrum.

Working with the architecture of the Artist Project Space at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, I designed twenty-four thin steel boxes of various sizes to encase the different shades of silk. As a whole the piece looks like a matrix of grids. As one looks through the layers of steel boxes reflecting the silk colors and moves deeper into the space, one experiences a blending and buildup of tones or pigmentation. In mixing the chemistry for the dyes and timing the silk dying, I made sure that no two pieces of silk are the same, just as no two people are the same.

Thanks

The exhibition is supported through grants from the Oregon Arts Commission, the Hallie Ford Foundation, and the Stillman Drake Fund at Reed College. I would like to thank Dr. Alexandra Stern for allowing me to use her research and for the important work she is doing in this field. Thanks also go to June Black and Jessi DiTillio, co-curators of the exhibition, for their patience and support during this long process. Special thanks go to Jim Schmidt for his work on the steel boxes, and a huge debt of gratitude goes to Cylvia Davis, my studio assistant, who helped me every step of the way. Thanks to Emily Johnson for her work laying out the gallery guide and Dan Kvitka for photography.

Materials and Process

Using steel and silk was of particular importance for this project. These two materials had enormous effects on the global economy and human relations and as a result, our genetic inheritance for centuries.

All silk is 100% pure. The dyes used were all natural dyes. Boxes: Mild steel, 18 gage, bent, welded, buffed and coated with matt finish.

Silk Aurora Silks, Portland Oregon

Illusion, 100% reeled natural silk. Source China

Peace silk, 100% hand-reeled silk filament. Source, Uzbekistan silk production is all done on micro family farms with mulberry trees up to 400 years old.

Dupioni Organza, 100% natural raw, reeled silk. Source, China

Cleopatra, 100% silk, reeled and especially tightly twisted for the weft. Source, China

Luninera Ahimsa, 100% Ahimsa TM Peace silk; long staple spun silk, plied warp and weft. Cultivated Bombyx mori, mulberry silk. All the Ahimsa TM silks are certified organically grown. Source, Silk raised in rural India on small family farms. Yarn is spun and fabric is woven in small mills in India. Aurora Silk is partnered with the patent holder in India.

Natural dyes: Aurora Silks, Portland Oregon

Brazilwood, sawdust from violin bow manufacturing, Brazil.

Colors: various shades of red, add iron mordant for purples.

Indian Lac, from the cochineal bug, India.

Colors: deep shades of red.

Longwood, saw dust from milled Longwood, Mexico

Colors: Full range of purples, shades vary according to the amount for alum and or iron added. Black, prepared with tannin and iron.

Fustic wood, fallen branches, Caribbean Islands and Dominican Republic.

Colors: yellow, golds, oranges.

Curator's Statement

In the 1927 case Buck v. Bell, the United States Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of involuntary sterilization. The plaintiff, Carrie Buck, an inmate at a Virginia state mental institution, had been ordered forcibly sterilized for being “feeble-minded.” Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, referring to Buck, her mother, and her daughter, infamously penned the lines, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”1 Carrie Buck was just one of more than 60,000 state-sanctioned sterilizations performed in this country from the early 20th century through the 1980s. Shockingly, this practice was hailed by one of the country’s major newspapers in the 1930s as a “protection, not a punishment.”2

The “eugenics craze” of the Progressive Era provided the cultural climate necessary for Buck v. Bell to end in Carrie Buck’s sterilization. Eugenics, a pseudo-science developed in the 19th century, sought to improve the so-called genetic quality of the human population through encouraging reproduction by people with preferred genetic traits and discouraging reproduction by people with less desirable traits. This was accomplished through abortions, forced sterilizations, and—at its most horrific extreme—euthanasia and genocide. Although these practices are most often associated with Nazi-era medical abuses, the United States is equally culpable for instating discriminatory laws that targeted individuals based on supposed links between genetics and moral fitness. In Oregon alone, more than 2,600 sterilizations were performed between 1917 and 1983. It was not until 2002 that Governor John Kitzhaber publicly apologized for what he described as the “misdeeds that resulted from widespread misconceptions, ignorance, and bigotry” and declared December 10th Human Rights Day in Oregon.3

For many years, Geraldine Ondrizek’s art practice has explored personal and political issues related to genetics, ethnic identity, and disease. Now, in this special exhibition created for the Artist Project Space at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, she responds to the history of eugenics in the American West with Shades of White. Using steel and silk—two of the most significant materials in shaping world history—she reinterprets the “Gates Skin Color Chart” used by proponents of eugenics in the mid-20th century. In doing so, she critiques the practices made possible by the pervasive employment of eugenics, such as the forced sterilizations that began with Carrie Buck. Rigorously researched and thoughtfully executed, Ondrizek’s installation invites viewers to look through the silk panels, designed to approximate variations of skin pigmentation, and consider their own ideas about race and identity. Her appropriation of this eugenic device to facilitate a discussion of human dignity is poignant and timely. We at the museum are deeply grateful to Geraldine Ondrizek for sharing her perceptive work with us.

June Black, Associate Curator

Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

Footnotes

- Buck v. Bell 274 U.S. at 207 (1927).

- Fred Hogue, “Social Eugenics,” Los Angeles Times (Sunday Magazine), Jan. 19, 1936, quoted in Alexandra Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 83.

- “Full Text of State’s Apology Regarding Eugenics,” (Oregon) Statesman Journal, Dec. 3, 2002, quoted in Stern, Eugenic Nation, 1.

- Dr. Alexander Stern, Genetic Counseling in Modern America: Gender, Race, Risk and Biomedicine in the Twentieth Century. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.