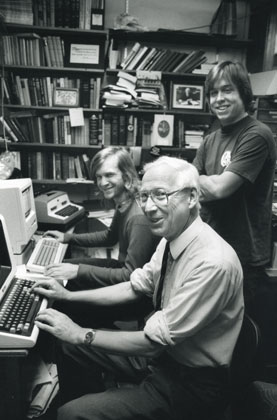

John Edward Herbert Hancock, Faculty

Courtesy of Special Collections, Eric V. Hauser Memorial Library, Reed College.

John Edward Herbert Hancock, professor of chemistry at the college for 34 years and well-known for his commitment to teaching and his involvement in music, died Thursday, March 16, 1989, of a heart attack. He was 59.

Hancock came to the college in 1955 and spent his entire professional career here. He was universally admired for his commitment to teaching, his scholarly research, and his exacting attention to detail.

He was an authority on electrochemical syntheses and the chemistry of azides, azo compounds, and nitrenes. He was fascinated with the application of computers to chemical problems and once served as director of the college's computer center. His sympathy for students' difficulties in learning organic chemistry led to his development of the first organic chemistry computer drills for the Digital Equipment Corporation's VAX computer and UNIX systems.

His academic achievements included a Fulbright Scholarship, postdoctoral fellowships at Harvard and Yale Universities, and the Hofmann Prize in Organic Chemistry. A prolific writer, he published widely in the field of organic chemistry, often with Reed College students as coauthors.

Professor Hancock had received research grants from Linus Pauling, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Science Foundation, among others, and he once served as consultant to the Dow Chemical Company. He was a member of several professional organizations, including the American Chemical Society, the Chemical Society of London, and the American Guild of Organists.

A lover of music, Professor Hancock in the 1960s cofounded the Collegium Musicum, a Reed group of singers and instrumentalists who perform Early Music. He was also an accomplished photographer.

Bom in the county of Warwickshire, England, Professor Hancock graduated with first class honors from the Imperial College in London and also held the degrees of PhD, ARCS, ARIC, and DIC from that institution.

Surviving are his sister, Nora Unwin, of Attenborough, England, and his niece, Penelope Unwin, of Sydney, Australia.

Tackling "The Mt. Everest of organic synthesis," and making a computer from pinball machines

[Excerpts from the Faculty Resolution Honoring the Memory of John Edward Herbert Hancock; drafted by Marshall Cronyn ’40, vice president & provost and professor of chemistry]

Very early in his career, John began to focus his research efforts on the synthesis of a molecule having the shape of one of the five regular polyhedra. The molecule is dodechedrane, a symmetrical C20H20 hydrocarbon with 12 faces, 20 vertices, and each side pentagonal. In degree of difficulty, this project was rather like an assault on the Mt. Everest of organic synthesis being carried out with a small band of undergraduates and no retinue of porters. A few years ago, when the synthesis was finally accomplished by a group in a large midwestern university, it had required over 150 full-time graduate student and postdoctoral research years.

John's interest in dodecahedrane led him in 1960 to construct the first computer used at Reed College. He wanted to calculate the number of isomers, which would be possible with the replacement of hydrogen on dodecahedrane by other elements, such as chlorine. john constructed the computer from pinball machine parts supplied by the Portland Police Department from illegal machines that they had confiscated. Since the machine performed only one function, john called it DIMWIT, for "Dodecahedrane Isomer Machine With Internal Translation."

In the past few years there has surfaced again the perennial renewal of a national concern for the improvement of college students' writing. A call for more attention to writing across the curriculum has been voiced. Throughout his teaching career, John never ceased his Sisyphian efforts against the hard rock of his student's writing deficiencies. Laboratory reports, the annual paper in organic chemistry, junior qualifying exams, and the senior thesis were all vehicles for John's unflagging efforts on behalf of accuracy and clarity of expression. For his students' benefit, he published a "Short Guide to Chemical Writing" and an introduction to the chemical literature.

Without fail, after a thesis had survived the critical review of other faculty readers, John would find a dozen or more errors—scientific, grammatical, or spelling. His criticisms of student writing were never personal, never a putdown. They were precise, constructive, and leavened with a droll and witty humor, a playfulness with words, even a pun or two in the margin; or, as John would have hastened to add, they were marginal puns.

During a time of continuing changes in the theoretical structure of organic chemistry and in the nature of chemical instrumentation, john kept abreast of these currents and maintained a steady incorporation of this material into his teaching. He became well acquainted with each new scientific instrument, in its theory and practice, just as with the ancient musical instruments he discovered and learned to use.

In his contributions to the teaching of science, to the musical life and other affairs of the college, John E.H. Hancock was, withal, a Renaissance man, an Englishman, a gentle man, and a gentleman.

J.E.H.H.: Elegy

by Richard C. Roistacher ’65 (May 30, 1989)

Oh John, I was not ready for this news,

Alumni rags should bring us word of births,

Accomplishments, achievements, and new things.

My class does not yet brook mortality.

It seems there was so much for us to say,

And yet we both kept silent for fifteen years,

So now my voice bewails your silent voice,

And memory takes experience’s place.

You sought dodecahedrane, and my part,

To pry those comic relays from their frames,

Festooned with wires like Einstein’s wispy hair,

To be reborn as DIMWIT’s neural cells.

“Dodecahedrane, what would it be like?”

I asked. You said, “A heavy paraffin.”

But not so heavy as the molecules

Of paraffin that choked your English heart.

Paper chromatography to find

Constituents in ordinary ink.

My second lab report, and you replied,

“Blank verse? How can that be? It doesn’t rhyme.”

We did not share a discipline, for I

Failed every course in chemistry I took,

And yet, I know more chemistry today,

Because of you, than many who had “A”s.

What we shared was empathy of mind,

And decorous excursions to the mad,

Monty Python played in both our hearts,

Years before it ever hit the tube.

Your greatest lecture, on the TV news,

“Lead azide, an explosive that should not

Be left in basement rooms in women’s dorms,”

Declaimed in tones most professorial.

While I, your faithful sidekick, looking tough,

Bedecked with fuse and blasting caps, prepared

To give the tiny vial its coup de grace,

With seven pounds of composition C.

We did it all without hint of smile,

Ann Shepard, who had sent you to maintain

Reed’s dignity was not amused. (My God,

She’s also gone, so many years ago.)

When after fifteen years we met and shared

Perplexity and grief at loss of love,

Youth and mentor changed to man and man,

Tutelage to friendship, face to face.

Oh, John, I was not ready for this news.

You’ve been with me these years, but far away,|

And now you’re with me in my solitude.

Appeared in Reed magazine: May 1989

![Photo of Prof. Marvin Levich [philosophy 1953–94]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2022/LTL-levich1.jpg)

![Photo of President Paul E. Bragdon [1971–88]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Bragdon.jpg)

![Photo of Prof. Edward Barton Segel [history 1973–2011]](https://www.reed.edu/reed-magazine/in-memoriam/assets/images/2020/Segel.jpg)